| This site celebrates the life and work of sculptor John Cassidy (1860 - 1939). |

Share this

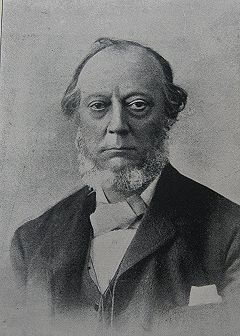

Henry Edward Schunck (1920 - 1903). From a photograph by Lombardi & Co. Pall Mall, London, circa 1889.

The Schunck family

The Schunck family first settled in Manchester in 1808, when Carl Schunck, an officer in the army of the Elector of Hesse who had fought on the British side in the War of the American Revolution, moved to England from Malta. He founded the firm of Schunck and Mylius, one of the first of the textile 'shipping merchants' which became the stock-in-trade of Manchester City Centre.

German merchant Carl Cornelius Souchay (1768-1838) married Helene Schunck, and the firm became Schunck, Souchay and Company. The family and business relationships of the Schunck, Souchay and Mylius families and Germany were complex, with interlocking families and business in Germany and Britain.

(Incidentally, Carl Souchay's daughter Elisabeth married famous composer Felix Mendelssohn, who is known to have visited the family in 1847 at their home in Didsbury, south Manchester, which they named 'Eltville' after the German town where they owned a vineyard.)

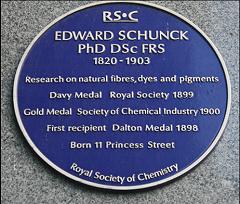

Carl's son Martin Schunck (1788-1872), joined the firm and was delegated to run a Manchester branch of the export merchant business, which developed to include textile manufacturing. He married Susanna (Known as Nanny), daughter of Johann Jacob Mylius, a senator of Frankfurt am Main, and they had seven children; Henry Edward Schunck (he never used his first name) was born on 16 August 1820, at the family home, 11 Princess Street, Manchester.

A blue plaque adorns a building on the site of the Princess Street house, on the corner of Albert Square, where a Victorian office building now stands.

Martin Schunck lived for a while in an old house called Wicken Hall, in the village of Ogden, near Rochdale, close to the firm's Wicken Hall bleach and dye works.

The 1841 census shows Martin, Nanny and Daughter Julia living (with a team of servants) a large house called 'Chorlton Abbey' in Greenheys, then a semi-rural part of Chorlton-on Medlock just to the south of Manchester, featured at the beginning of in Elizabeth Gaskell's first novel Mary Barton published in 1848:

There are some fields near Manchester, well known to the inhabitants as "Green Heys Fields," through which runs a public footpath to a little village about two miles distant. In spite of these fields being flat and low ... there is a charm about them which strikes even the inhabitant of a mountainous district, who sees and feels the effect of contrast in these common-place but thoroughly rural fields, with the busy, bustling manufacturing town he left but half-an-hour ago.

The Schunck and Gaskell families were on friendly terms, judging from letters that have been preserved.

Edward was educated privately in Manchester, where he was was introduced to practical chemistry by William Henry (1774 - 1836), author of the gas solubility law, and in Germany where he studied chemistry at Berlin University and took a PhD from the University of Giessen under its most famous member Justus von Liebig, the founder of modern agricultural chemistry and inventor of artificial fertiliser.

He returned to England in 1841 and the post of manager of the company's Belfield Mill, in Milnrow, near Rochdale which engaged in fulling, bleaching, dyeing and calico printing. He appears to lived in an old mansion called Belfield Hall at this time.

However, it was decided that he should concentrate on his scientific work, and a new works manager was found. He published his first research paper in 1841 and he devoted the rest of his life to investigations into the chemical composition of natural dyes and pigments, including madder and indigo. Funded by the family fortune, he made a career as a 'gentleman scientist'.

Schunck was a founder member of the Chemical Society of London in 1841. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society on 6 June 1850 and he was Davy gold medallist for 1899. Elected into the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society on 25 January 1842, he was secretary (1855–60), and president (1866–7, 1874–5, 1890–91, 1896–7), receiving in 1898 the society's Dalton bronze medal (struck in 1864 but not previously awarded). He was also an original member of the Society of Chemical Industry (1881), chairman of its Manchester section in 1888–9, president in 1896–7, and gold medallist in 1900 for his conspicuous services in applied chemistry. In 1887 he was president of the chemical section of the British Association at the Manchester meeting. He was deeply interested in travel, literature, and art, and in works of philanthropy connected with his native city.

Fellow Members of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, included James Joule (subject of another Cassidy work) and Lyon Playfair, another Manchester industrial chemist who became an academic and later moved to London and greater fame, and was commemorated in the name of the Lyon Playfair Library of Imperial College, once a haunt of the present writer.

Schunck's chemical samples, preserved in the Museum of Science and Industry, Manchester, 2017.

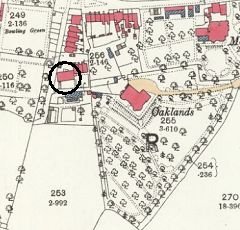

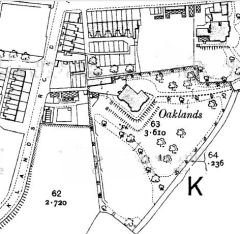

On 1 October 1851 Edward Schunck married Judith Howard Brooke, and by 1861 the couple were established in a large house, 'Oaklands' in Vine Street, Kersal, Salford with five children aged between 1 and 8 years, along with a French governess, a coachman, groom, cook, two housemaids and two nurses.

The 1901 census shows the household as Edward, his wife Judith Howard Schunck and seven servants: a butler, four housemaids, a cook and a 'sick nurse'.

Edward Schunck died at his home on 13 January 1903, and was buried in St Paul's churchyard, Kersal. (Sadly, his gravestone has toppled forward, and cannot now be read). His wife, three of his five sons, and one of two daughters survived him.

A a nurse was still on the payroll at Oaklands in 1911, where Mrs Schunck was residing alone - except, that is, for a lady companion, the nurse and six other servants, all female. She died in 1918 aged 92.

Schunck's will

(From a newspaper report, 1903)

The will (dated Nov.14, 1899) of Mr Henry Edward Schunck, Ph.D, F.R.S., of Oaklands, Kersal, Higher Broughton, who died on Jan. 13, was proved on March 3 by Martin Hubert Schunck, John Edgar Schunck, and Charles Adalbert Schunck, the value of the estate being £148,134. The testator gives the land with the laboratory and buildings thereon adjoining his residence, and the apparatus, instruments, specimens, books, etc. to Owens College, Manchester for the study of and research in chemistry, both for men and women. He also gives £1000, an annuity of £3000, and the use and enjoyment of Oaklands to his wife Mrs Judith Howard Schunck; £10,000 in trust for his daughter Mrs Catherine Marston; certain ground-rents at Greenheys to his son Charles Adalbert; and legacies to servants. On the death of Mrs Schunck he gives Oaklands to his son Martin; and the residue of his property he leaves to his three sons.

The next generation

Brief details of those of Edward Schunck's children, who lived to adulthood. The 'family fortune' seems to have played a large part in all their lives.

Juliet Dorothea Schunck, born in 1852, died, unmarried, in 1886.

Martin Hubert Schunck (born c.1853), who like his father preferred his second name to that of his grandfather, left home and lived with his wife Gertrude in various parts of the country. He was in 'agricultural pupil' in Suffolk in 1881, was 'living on own means' in Suffolk in 1891, was a yarn export merchant in Harrogate in 1901 and 1911, and died in 1916.

John Edgar Schunck (c.1857 - 1931) stayed in Rochdale to run the family factory; in 1881 he was living at Wicken Hall. In 1901 he was 'living on own means' near Buxton.

Catherine Schunck, born in 1860, married Oswald Charles Marston in 1884. Marston was a 'merchant's clerk' when he was recorded living with the Schunck family in Bromley, Kent in 1881 - presumably a family holiday. Catherine died in a nursing home in Newton Abbot, Devon in 1943.

Charles Adalbert Schunck, born in Kersal in 1865, studied at London and Cambridge Universities. He is known to have assisted his father with his laboratory experiments. He married Bertha Clarissa Howard in 1898, and later they lived in Oxfordshire where he died in 1936, and she died in 1945.

Postscript: Soap story

After the death of Mrs Schunck the house 'Oaklands' was sold to Alexander Tom Cussons, born in Yorkshire in 1875. He served an apprenticeship as an electrical engineer, but by 1901 was in business as a 'wholesale chemist' in Swinton, near Manchester, and by 1911 Cussons, who by then was describing himself as a Manufacturing Chemist, living with his family at Halliwell House in Prestwich, north of Manchester.

In 1920 he established a soap factory in a former bleachworks on Moor Lane, Kersal Vale, and the following year he acquired pefumier Bayleys of Bond Street, and in 1938 used one of their original perfumes, 'Eau de Cologne Imperiale Russe', to create Cussons' Imperial Leather soap which is still a well-known brand in the twenty-first century.

Edward Schunck's former house 'Oaklands' was within walking distance of the Cussons factory and he made his home there, building a range of glass-houses for his collection of rare orchids. Regrettably, the house was badly damaged and much of the orchid collection destroyed when a bomb landed at the bottom of the garden during the Blitz of 1941. Cussons died in 1951.

In 1976 the Cussons company was taken over by multinational firm PZ in 1976, and in 2017 trades as PZ Cussons. The factory was demolished in 2010, but PZ Cussons continued to manufacture Imperial Leather and other products at a new works in Agecroft, Salford.

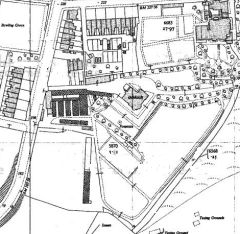

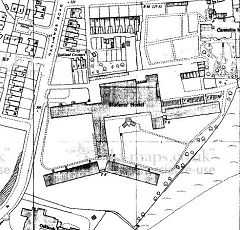

Oaklands in maps

Oaklands estate in 1893. We believe Schunck's laboratory is the structure we have circled ...

... as it has gone by 1908. A new through road, 'Oaklands Road' had been created.

This 1952-dated (although possibly from a pre-war survey) shows the glasshouses erected for the Cussons orchids. Part of the house has been removed.

1969: Everything has been removed, except the workers' cottages adjacent to the laboratory site, replaced by the Oaklands Road Halls of Residence, built for Salford University (below).

This view of the halls from the Salford University archive shows the elevated location of the Oaklands estate, on the bluffs above the Irwell river.

The halls of residence were, in their turn, swept away and replaced by houses. Culs-de-sac called 'Degas Close' and 'Manet Close' now occupy the site of Oaklands.

Henry Edward Schunck memorial (1904)

John Cassidy's portrait medallion of Edward Schunck, now on display in the concourse of the University of Manchester's Chemistry building, has been revived after a period of obscurity.

In its issue of 9 July 1904, the British Medical Journal reported:

After the meeting of the Court of the University of Manchester on July 1st [1904], the Schunck Laboratory for Chemical Research was opened by Dr. Perkin, senior. The laboratory has been removed from Kersal and erected just as it was in Dr. Schunck's lifetime. Along with the laboratory was given to the University the library of technical works and periodicals dealing with chemistry and a fine collection of chemical specimens relating to "that department of chemistry which embraces the colouring matters" with which Dr. Schunck's researches were mainly concerned. The laboratory will be used entirely as a research laboratory. A fine medallion portrait of Dr. Schunck was presented by his widow.The Manchester Guardian reported the opening in detail, including the unveiling of the portrait (with no mention of Cassidy):

The company then went to see the extensions to the College Laboratories, as well as the laboratory bequeathed by Dr. Schunck. In the room which had formed Dr. Schunck's library there is a medallion portrait of the Doctor. It has been presented by Mrs Schunck as a memorial of the late husband, and was now unveiled and presented to the University by Mr Charles Schunck on his mother's behalf.The above is all we know about the commissioning of the work. Based on known quotes for other works, Cassidy would have charged about £60 for a bronze medallion of this kind; it depicts him in the academic robes of a Doctor of Science.

The Vice Chancellor said he had received a letter from Mrs Schunck. She wrote:- "I have great pleasure in presenting the Schunck Laboratory with a medallion portrait of my beloved husband the late Dr. Schunck, whose devotion to science pervaded his whole life, and whose example will, I hope, be a stimulus to the efforts of those students whose work follows the lines of scientific research." Mrs Schunck added an expression of her best wishes for the increasing prosperity of the Manchester University.

Mr. E.J Broadfield accepted the medallion in the name of the court and Council of the University. It was, he said, a valuable addition to the the artistic memorials of Owens College worthies. While they looked upon it as a counterfeit presentment of a a great man who held a high place in the history of research and of practical chemistry, some of them would associate it with the honoured father of the late Dr. Schunck, who worthily represented the best traditions of the commercial life of Manchester.

Our records show that this work was not Cassidy's only portrait of Schunck. A marble bust was exhibited at the Manchester Academy of Arts annual exhibition in 1902 (no.289) and again in 1919 (no. 258). Perhaps the bust was modelled from life, as Schunck was still alive in 1902.

The medallion recorded here was exhibited at the Manchester Academy of Fine Arts exhibition in 1911, and also at Cassidy's own exhibition at his studio in 1914 (possibly a plaster model), along with medallion in silver, possibly a small medal-size version for family members and colleagues. These are as are known to exist in other cases. Manchester Guardian reviewer 'B.D.T' writing of the 1914 mentioned the bronze work: 'A large relief portrait of Dr. Schunck is ... excellent in its realisation of character in a profile'. We have no knowledge of the later whereabouts of the silver version; the marble bust may possibly have been one of those displayed in the Library (see below). Any information on this subject is very welcome.

Other images of Schunck are hard to locate: the one shown here was originally published in 1998 in the Journal Manchester Faces and Places. He is included in a group photograph with Henry Roscoe, Dmitri Mendeleev, and Georg Hermann Quincke, taken at British Association meeting, Manchester 1887, reproduced in an article in the John Rylands Library blog.

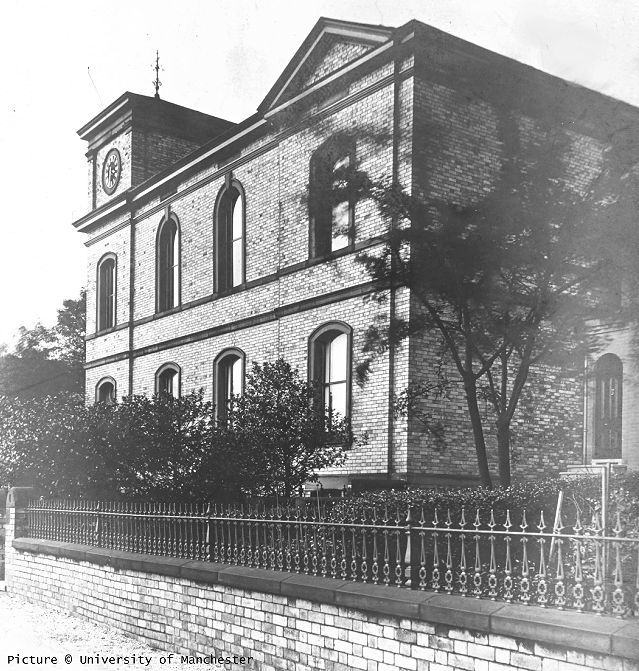

The building

This picture shows the Schunck laboratory building in its original location...

... and this one shows the building on Burlington Street in 2014 when the basement was in use as a vegetarian café. It was rebuilt adjacent to the Chemical Laboratory, which had been built soon after Owens College moved to the Oxford Road site in 1873. The re-located building is a apparently a mirror-image of the original, as the window spacing is different and the door is in a different place. To the right is the Schorlemmer Laboratory of 1895, designed by Alfred Waterhouse, and to the left the University Library extension completed in 1981. The library extension is built across Burlington Street, which previously continued through to Lloyd Street.

The work was carried out by William Southern & Sons, Builders, of Salford, to whom we owe the existence in the University of Manchester archive of a set of pictures of the Kersal building, including the interiors after the contents had been removed. All the photographs, and their accompanying letter, can be viewed on the University Library's 'Luna' image database - search for Schunck. We are grateful to the Library for allowing us to reproduce some of them here.

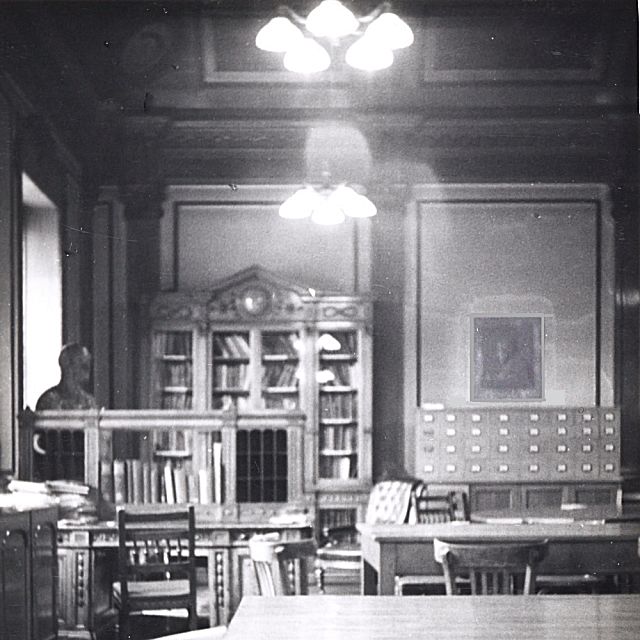

This one shows the first floor library at Kersal with its zodiac paintings which were re-created in the Library after the removal of the building to Manchester. The elaborate metal structure is perhaps a gas supply for lighting.

It has been suggested that the building was built new in the style of the original, as the colour of its bricks matches other buildings along Burlington Street. The architectural details closely follow the original, however; the work was planned by Paul Waterhouse, whose father Alfred Waterhouse was responsible for many of the buildings around the University quadrangle. To the left is the University Library extension, opened in 1982, and on the right the former Schorlemmer Laboratory of 1895. When first installed, the building's neighbour was the Eagle Brewery, which practised another sort of chemistry.

The front doorway has Henry Edward Schunck's monogram and the date 1871, the building date of the original. A set of Waterhouse's original drawings of the original and re-erected buildings survives in the collection of the Royal Institution of British Architects and can be viewed online.

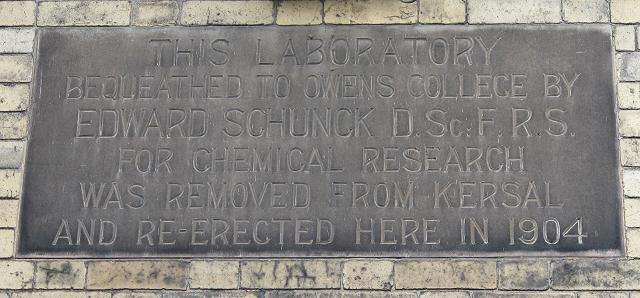

The plaque on the front wall. The following is an extract from a long article in the Manchester Courier of 2 May 1906, page 10, praising the state of chemical research at the University:

The wonderful feature of the Manchester laboratories beyond their extent is the number of excellent separate laboratories, in which two or three students may quietly and thoroughly conduct experiments that are long and wearisome and exacting. Of these there are upwards of a dozen, to say nothing of the excellent Schunck laboratory, with its basement and its wonderful library, the whole structure of which was bodily removed from Kersal and re-erected under the direction of Professor H.J. Dixon. To him, perhaps, sufficient recognition has not been paid for the service he rendered in securing the site on which he building in its completeness from basement to roof stands just as it stood in the testator's grounds. Incomparable on every floor as a private laboratory, it is now doing invaluable public work, while the library that forms part of it is unique with its collection of books on science. The library is being kept up to date, all the works of which annual volumes are published being continued.

It has a richly furnished appearance, with floor and doors of inlaid expensive woods, and here and there are medallions and busts of famous men, and last, but not least, Dalton's own arm chair. A young student reading at ease his "Roscoe and Schorlemmer" was surprised on our visit to be roused by the director and told that he occupied for once the chair of Dalton.

Schunck's bequest included the books from his library, and the Victoria University of Manchester, as it had become by 1904, preserved the Library on the upper floor of the building as a Library for the Chemistry Department, and Cassidy's medallion was installed there; it can be seen in this photograph, which we have digitally enhanced to bring out a little of the detail of the work, as its bronze patination did not show well in the original image. The curved zodiac paintings at ceiling level can be glimpsed.

A bust is visible in the corner of the room, and photograph taken looking the other way shows there was another bust at the other end, and a large oil painting on the wall. Is one of these the bust of Schunck made by Cassidy? It is very hard to tell from the resolution of the small image available.

When the new Chemistry building was built on Brunswick Street in the 1960s, the old buildings, including Schunck's laboratory, found new uses, including offices for the University administration. The Schunck building became the headquarters of the Burlington Society, a social club for postgraduate students, and was re-named the 'Burlington Rooms.' The ground floor laboratory became a bar and performance space, while the library above was used as a common room and retained many of its original Schunck features, including the paintings of signs of the Zodiac around the walls, and even the Cassidy medallion. In 1974 it was classified as a Grade II Listed Building, protecting it from any significant changes.

Viewed from the fourth floor of the University Library, the slate roof of the Schunck Building contrasts with the red tiles of most of its Victorian neighbours.

The 'Herbivore' vegetarian café moved in to the basement some time in in the 1990s, but the rest of the building, along with the complex range of old university buildings, became largely vacant; by 2013 the University had developed a plan to bring them all back into use. The café moved out to a new home in the Contact Theatre, and in 2014 Planning Permission was sought for the proposed development; the planning application is available online, and includes fascinating historical detail about all the buildings. Around this time, the building officially became the 'Schunck Building' although it is consistently spelled as 'Schunk' in all the Planning documents.

The

planning documents include a very

extensive photographic survey of the interior buildings as they were in

2014. Unfortunately, the photographers were not able to gain access to

the Library room. The document does include a small, un-dated,

photograph (reproduced here) of the room, presumably as it was when in

use by the Burlington Society. It is clear that the medallion was still

in position. However, a comprehensive list of artistic material

belonging to the University compiled in 1975 by William Brockbank

records the work as 'stacked in the old chemistry building'.

The

planning documents include a very

extensive photographic survey of the interior buildings as they were in

2014. Unfortunately, the photographers were not able to gain access to

the Library room. The document does include a small, un-dated,

photograph (reproduced here) of the room, presumably as it was when in

use by the Burlington Society. It is clear that the medallion was still

in position. However, a comprehensive list of artistic material

belonging to the University compiled in 1975 by William Brockbank

records the work as 'stacked in the old chemistry building'.Revival of the Medallion

Fortunately, in 2012 Professor Jonathan Connor, the Chemistry Department's honorary archivist, became aware of the existence of the Cassidy work, and arranged to have it cleaned and re-located in the current School of Chemistry building on Brunswick Street. Unfortunately, perhaps, the cleaning removed its original bronze patina, although its new bright brassy appearance might catch the eye of passers-by. The picture above shows it in its new location, with interpretation board.

The Chemistry Department also owns this small version, about 20 cm across, which was possibly cast from a model made by Cassidy as a suggested layout. It differs significantly from the larger version in that Schunck is facing right rather than left. Perhaps Mrs Schunck felt that the left side was his 'best side.' It is thought that this version may at some time have been on display in the library of the new building, known as the Schunck Library.

Schunck's books from his bequest are now housed in the John Rylands Library's Special Collections department.

A 2014 view of the exterior of the current Chemistry building, designed by the firm Harry S. Fairhurst and Son and built by the form Holland and Hannen and Cubitts between 1962 and 1965, after alteration to gain 'reluctant approval' by Manchester Corporation Planning Committee whose chairman described the design as 'nondescript' and a 'glorified warehouse'.

Unfortunately a recent re-design of the entrance area conflicts with the relief mural, said to have been designed by German-born artist Hans Tisdall (1910-1997), possibly inspired by John Dalton's atom symbols of 1803.

Selected references

James Peters, Edward Schunck and the History of Dyeing, John Rylands Library Special Collections Blog, 2017

Henry Edward Schunck: website by Chris Cooksey Includes a full Schunck bibliography.

H.B. Dixon: Edward Schunck, 1820-1903. (Available in University of Manchester Library).

St Paul's Church, Kersal Moor, Churchyard Trail (PDF)

T. E. James, ‘Schunck, (Henry) Edward (1820–1903)’, rev. Anthony S. Travis, first published 2004. Dictionary of National Biography.

Manchester Faces and Places, Vol. 9 no.1, 1897.

'Chemical Research ... Victoria University'. Manchester Courier, 2 May 1906, p.10.

'Death of Dr. Edward Schunck', Manchester Evening News, 13 January 1903, p.4

'Chemical Research; Opening of the Schuck Lanoratory', Manchester Guardian, 2 July 1904, p.6

Thanks ...

... to Professor Jonathan Connor, who rescued the work and welcomed me to the Chemistry building to view it, to Peter Wadsworth who facilitated my visit, to Dr Diana Leitch, MBE FRSC, former colleague and Didsbury local historian, for information about the Schunck family, and to the archivists and photographers of the Universtity of Manchester Libaries.Written by Charlie Hulme, March 2017. Comments welcome at charlie@johncassidy.org.uk