| This site celebrates the life and work of sculptor John Cassidy (1860 - 1939). |

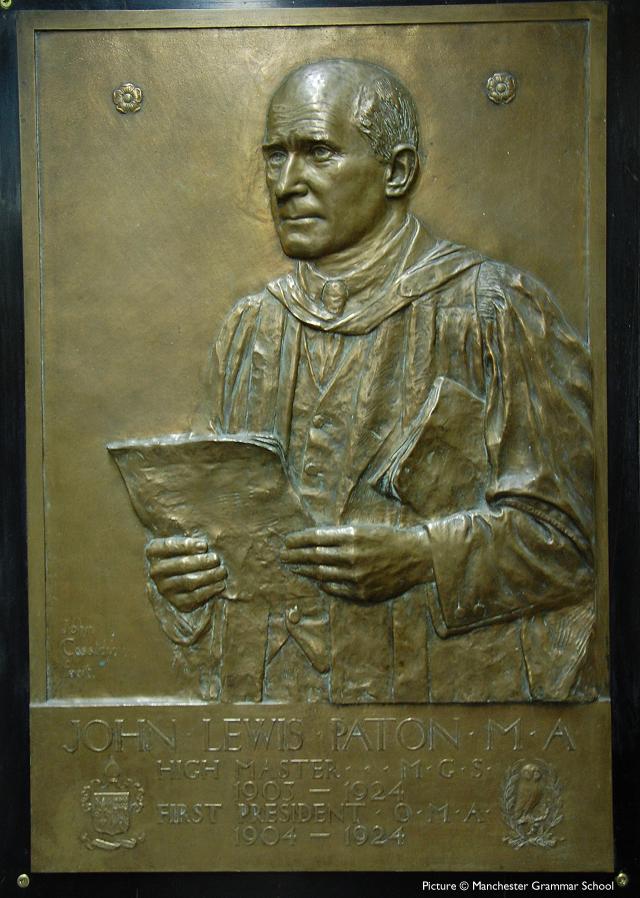

This work, a bronze portrait in relief - described at the time as a 'medallion' - along with a small number of small replicas, also in bronze, was commissioned in 1924 by the Old Mancunians' Association, the organisation for former pupils of Manchester Grammar School, a long-established school for boys which at the time was situated in buildings in Manchester City Centre. It re-located to its present site in Rusholme, south of the city, in 1931.

The work was created to mark the retirement of Paton as High Master, and is now displayed in the school's Paton Library which is named in his honour.

The medal

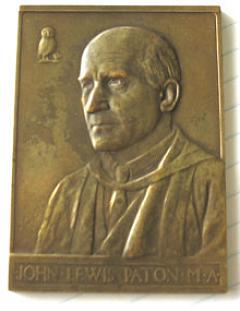

The present writer, Charlie Hulme, has a personal connection to the work. A small bronze 'medal' version of it (pictured above) now sits alongside where this is being written. In an auction held by Morgan Evans and Co., Gaerwen, North Wales on 27 February 2014, it appeared, unattributed, as 'Lot 165 – A Relief Bronze Portrait Plaque Of John Lewis Paton M.A.'

Soon afterwards it was noticed on an internet auction, and successfully bid for, by Dr Louise Boreham, a writer and researcher, whose grandfather was Louis Reid Deuchars (1870-1927), a painter and sculptor who was a contemporary of Cassidy and from 1896-1900 worked as assistant to George Frederic Watts and his wife Mary Seton Watts at their studio in Compton, Surrey. He later created the remarkable Glenelg War Memorial.

The medal is signed 'J.C. 1924' and having discovered its sculptor, with the help of Steve Parlanti, historian of the Parlanti Bronze Foundries, she kindly offered it for sale to us.

We have yet to discover any record of who originally owned this small work, or how many others were made: it is likely that they belonged to the main participants in the commissioning and presentation of the main work, including J.L. Paton himself. Perhaps one of them or one of their descendants retired to North Wales, as was common among the professional classes at the time. Probate records dated 1944 for the death of Paton's sister Mary show that her estate was administered by the District Bank in Llandudno, North Wales, which may be relevant.

Another copy, owned by Manchester Art Gallery, which retains its original green cloth bag, is one of a number of Cassidy items purchased in 1980 from the family of Cassidy's assistant. It is not on public display.

The Newfoundland copy

There is at least one other copy of the medal, as related in Memorial University of Newfoundland Gazette, Vol 40 No 4,October 11, 2007:

A commemorative medal featuring Memorial’s first president John Lewis Paton has ended up in the QE II’s archives division, following a circuitous route across England and North America.

The medal, dated 1924, was purchased by Richard Closson in 2003. The California resident picked up the bronze medal from a coin dealer in Stuttgart, Germany, on the online auction site eBay. When he discovered that Paton was Memorial's first president he e-mailed the University to see if there was an interest in it.

'I am … interested in getting the medal in the hands of someone who appreciates it,' he wrote at the time. In finding this medal, I was just concerned that a connection to the scholar it depicts could be lost without a little follow-up. There are probably plenty of situations where a similar medal languishes in a desk drawer, to be taken out occasionally and wondered about. Paton and this medal seem worthy of better.'

Mr. Closson was subsequently contacted by Bert Riggs, head of the QE II Library’s Archives and Manuscripts Division, who let him know that the library was very interested in the medal. 'The medal you have in your possession would certainly have a place of honour here,' wrote Mr. Riggs.

If anyone has more information about the previous owners of these two copies of the medal, or any others, we'd be pleased to hear from them.

Thoughts of 'J.L.P.'

From his entry in the Dictionary of National Biography:Paton's ideals, like those of his father, were strongly democratic and he encouraged pupils at his schools to perform acts of social service ... His belief in the dignity of manual labour was strongly held: at University College School he joined the boys in painting the railings of the school grounds at Neasden; and at Manchester he took part in the physical work of levelling a patch of ground to form the playing field.

From a report of a meeting of the Industrial Welfare Society, 1922:

Speaking of production by machinery, with its creation of monotonous and uninteresting toil, Mr. Paton said it might be that machinery was in a transitional stage, and that the evils arising from it would be removed by the employment of more and better machinery ... We had got today what he did not remember this country to have ever had before - an unemployment problem for adolescents; and it seemed to him that we ought to save our adolescents from unemployment by ... deliberately raising the age up to which education should be given.

From a speech at a Bolton Girls' School in 1934:

Over 100,000 young people between the ages of 14 and 18 were unemployed, and 'What does that mean in terms of human flesh and blood? It means something much worse than enforced labour. It means enforced idleness, and if you asked me which any sons of mine should be subjected to, I should say "Give me enforced labour." If you are not finding jobs for these boys and girls, Satan will find them jobs. Their education goes on, but it is a downgrade education, the education of the street corner - grossness, vulgarity, gambling, dirt, roughness - it means a whole generation growing up and coming to man's estate without have a chance of doing a useful day's work - and there is an education that comes of doing a day's work.'

Links and References

The Manchester Grammar School, 1515-1965. edited by J. A. Graham, B. A. Phythian. Google Books edition.

The History of MGS (Old Mancunians website).

H. C. Barnard, 'A Great Headmaster: John Lewis Paton (1863-1946)'. British Journal of Educational Studies, Vol. 11, No. 1 (1962), p. 5-15. Available on JStor.

J.L.P. - A Portrait of John Lewis Paton by his Friends

Compiled by S. J. Carew (Memorial University, 1968). Available online.

Obituary in Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, Vol.30, no.1, 1946 (available online)

Thanks

Special thanks are due to to Louise Boreham for discovering the medal, and to Joanna Badrock, archivist of Manchester Grammar School, for her enthusiastic assistance with photographs and archive information.

JOHN LEWIS PATON M.A. (1924)

Paton and Manchester Grammar School

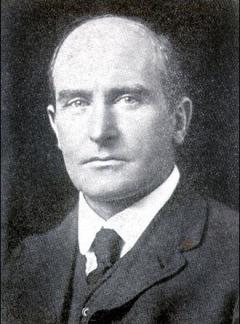

John Lewis Alexander Paton - he later dropped the Alexander, and informally preferred to be known as Lewis - was born in Sheffield, England, on 13 August 1863.

His father, John Brown Paton

(1830-1911) was serving as a Congregational Minister in the city at

that time of his son's birth, moving in 1866 to Nottingham to became

principal of the new Congregational

Institute there, a theological training college for Congregational

Ministers, a post he held until 1898. In later years the college was

renamed Paton Congregational College in his honour. His son John Lewis

Paton wrote a biography of his father, published in 1914.

Young John Lewis Paton was educated in Halle, Germany, at Nottingham High School and at Shrewsbury School where he became head boy. He entered St. John's College, Cambridge, in 1886 where he placed first in Classical Tripos, part two, with special distinction in Language and History, receiving the Junior Chancellor's Medal for Classics. He was made a Fellow of St. John's College in the same year. His teaching career began in 1887 when he became Assistant Master at The Leys School in Cambridge.

From 1888-98 he was Sixth Form Master at Rugby School. In 1898, aged just 35, he became the 'new, vigorous, young headmaster ... and enthusiast for phyical fitness' of University College School, Hampstead, London, retaining that post until 1902.

Chosen from fourteen applicants, he became High Master of Manchester Grammar School in 1903. The school, founded in 1515 by Manchester-born Hugh Oldham, Bishop of Exeter, to provide 'godliness and good learning' to the poor boys of medieval Manchester, was situated in Long Millgate in the centre of Manchester near the Collegiate Church, which is now the Cathedral. When Paton arrived, the school occupied two Victorian buildings joined by 'an inadequate and hazardous bridge' which crossed the entrance to the adjacent, and very historic, Chetham's School and Library. The newer of the two was built in the 1870s, to a design by Alfred Waterhouse, on the site of the original sixteenth-century building. It had no proper playing fields, and boys had to travel out to Fallowfield for ball games and athletics.

In 1931, after Paton's time (although he was involved in the early planning) the school relocated to a new site in Old Hall Lane, Rusholme, on the outskirts of the city, where it continues its mission 'to educate the brightest young men in the North of England regardless of their social, cultural, religious and financial background.' The Waterhouse building was taken over by the Chetham's School of Music and still exists, but the one on the other side of the footbridge has been replaced.

Paton never married; he wrote several authorative works on the subject of education, and gave himself entirely to his teaching. The 1911 Census records show him living at 'Arncliffe', Water Park Road, alongside Broughton Park, Salford with housekeeper Margaret Watson (born in Drogheda, Ireland), and servant Margaret Langley (born in Manchester). He had a policy of taking into his private house, as boarders, a few boys whom he specially wished to help, characteristically making no charge. Also listed are two boarders: Solomon Michaels, aged 22, and Carl Brammall Shrewsbury, aged 19; both were former pupils at the school who were studying Classics at Oxford University. Both men were later to experience the mayhem of the Great War, and Second Lieutenant Carl Shrewsbury of the Lincolnshire Regiment, son of a Methodist Minister, was 'killed in action' in 1915.

Professor H.C. Barnard, a former pupil of University College School, who later lodged with him while employed as a teacher at Manchester Grammar School, wrote in his fascinating memoir of the man:

He led the most simple of lives.

His bedroom, which was also his library, was lined from floor to

ceiling with books. It contained practically no other furniture except

a small, iron truckle-bed; though in summer J.L.P. usually slept out

under a 'bivvy' tent in the garden. He had practically no sense of

taste - a fact of which his aged housekeeper tended to take advantage;

though this sometimes made things trying for other members of his

household.

In 1924 he retired from his post in Manchester; it was at this time that the memorial plaque was commissioned from John Cassidy. It was modelled from life, Paton having been persuaded with some difficulty to sit for the scupltor, and as such is unlike many other such works, for which photographs had to be used as they commemorate the subject after death. One wonders whether Cassidy was chosen, rather that a portrait painter, because he was known to be able to capture a likeness in a single sitting.

On leaving Manchester, Paton travelled to Canada where he lectured at a number of universities and schools on behalf of the Canadian National Council of Education, and was appointed President of the Memorial College at St. John's, Newfoundland. He set up home there with his sister Mary Frances Paton, and stayed until 1932; in the words of his obituary in the Bulletin of the John Rylands Library:

He not only carried out his

duties of administration, but took more than his share in the work of

teaching. In Newfoundland, as in England, he found time to take a close

interest in matters outside his official duties. He saw the necessity

of developing the interest of the people in the study of the natural

resources of their country. Here he was an inspiration and a force, not

only in the college but in the wider sphere of Newfoundland life.

After his retirement from Memorial University, he returned with his sister to England where they made their home at 'Chalkway', Kemsing, Kent, where:

[From] 1939, with the noise of

the

Battle of Britain roaring overhead, he

laboured on, working for refugees, evacuees, the College of the Sea,

war savings, and on the land. In his seventy-eighth year he was once

more called back to the class-room to fill a gap in the ranks of

the teachers as an assistant master.

He made a number of return visits to England, and to Manchester after his second retirement, making speeches which were reported in detail in the back issues of the Manchester Guardian. His last visit to Manchester was in 1941 when he delivered the Memorial Lecture in the John Rylands Library, entitled 'The Tercentenary of Comenius's visit to England, 1592 - 1641', the text of which was published in the Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. It was 'a noble tribute of probably the greatest educationist of this century to the greatest educationist of the seventeenth.'

His sister Mary died in 1944, and he went to live with another of his sisters, Mrs T.P. Figgis, in Beckenham, where he died on 28 April 1946, and was buried three days later. He left an estate worth £28,241 19s. 4d.

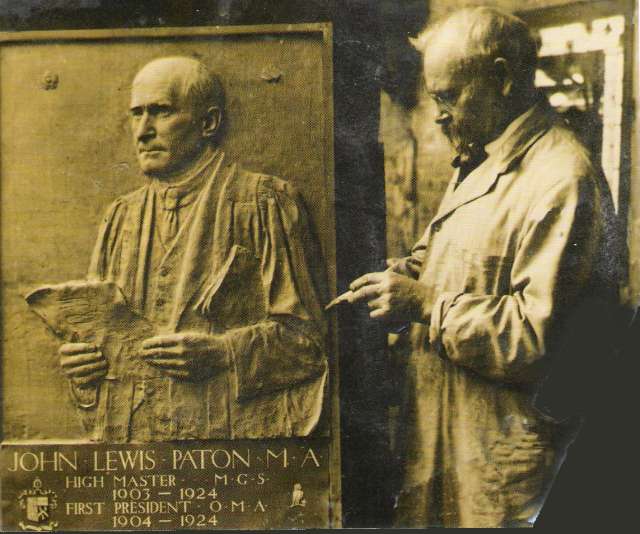

The Making of the Mediallion

This photograph, in the collection of the Slane History and Archaeology Society, shows Cassidy in the Lincoln Grove studio with the clay model from which the final bronze would be made. He was photographed in this way with several of his larger works. This picture is probably the latest in date; Cassidy was 64 years old at that time, but still busy with War Memorial work.

The 'nearly completed' clay version was displayed to 'subscribers and friends' at Lincoln Grove for two days, 1 and 2 October 1924; possibly the photograph was taken then. A photograph of the model alone appeared on page 10 of the Manchester Guardian of 1 October, with comments by the paper's regular art critic 'B.D.T.' (Bernard Douglas Taylor, himself an 'Old Mancunian'):

The variations of expression on the faces of great men are often carefully noted, and those of great schoolmasters are probably more exactly studied than the expressions of any other men. Possibly many people will miss this or that familiar look on Mr. Paton's face, but Mr. Cassidy has given to his portrait a very familiar likeness, and in the set of the figure as well as in the head he has managed to convey a great deal that is characteristic of his subject. He has handled the problem of relief well, also, and his model is carefully calculated for the final effect in the bronze cast.

An item in the same newspaper of 19 December 1924 mentions that the bronze version is to be exhibited in the Manchester Art Gallery 'for a fortnight.'

Included in the composition are representations of the red rose symbol of Lancashire, the coat of arms of the school, and the Owl symbol representing the Old Mancunians' Association, itself inspired by the owl on the crest of Hugh Oldham, Manchester-born Bishop of Exeter who founded the 'Manchester Free Grammar School for Lancashire Boys' in the year 1515. The small version retains only the owl.

The Paton Library in 2014.

The Presentation

Manchester Guardian, 21 March 1925, page 15.MR. J. LEWIS PATON.

PORTRAIT PLAQUE FOR THE GRAMMAR SCHOOL.

At the Manchester Grammar School last evening, Mr. Douglas Miller, High Master, as president of the Old Mancunians' Association, handed to the Governors of the school a bronze portrait plaque of Mr. J.L. Paton, who retired from the High Master's office last year. In the absence of the Chairman of the Board of Governors (Sir Arthur A. Haworth), Col. Westmacott accepted the gift. The plaque, the work of Mr. John Cassidy, and recently exhibited in the City Art Gallery, represents in high relief Mr. Paton in academical dress, reading from a document.

Mr. Miller said the Association were quite aware that the best memorial of Mr. Paton was not one carved in stone or bronze, but the one that was stamped on the heart and imagination of all who knew him. (Hear, hear.) They always remembered him as a man to whom life was service, who used his abundant energy to further the good, to establish the strong, and to help the weak, and who by the ideals he inspired, made that school a tower of strength, not only in the North of England, but far beyond.

But the Association felt that as a new generation arose and came to take its place in the school, it would be a help and an inspiration to them not only to hear what a great man did for the school, but also to have some representation of his features, and so - it must be admitted , with a little difficulty - Mr. Paton was persuaded to sit for the plaque. Col. Westmacott was asked to accept it and to have it hung in a suitable place on the walls.

Col. Westmacott, in accepting the gift, said the Governors, as well as the Old Mancunians, felt very proud that Mr. Paton had been able to leave a representation of his features behind him, for they had almost despaired of getting one. Though this was not necessary for those who worked with him on the Board of Management, who had passed through his hands, or who as masters had worked with him all these years, yet it was desirable that Mr. Paton's memory should be preserved in a form that would remind those who came after him and them what he was to Manchester and to that school. In the present school and in the new school the plaque would be given a most suitable position.

Mr. Douglas Miller [Douglas Gordon Miller, Paton's successor as High Master] said that every master and every boy in that school would treasure this memento of Mr. Paton with very great affection and very great pride. (Applause.)

From Ulula, Manchester Grammar School Magazine, 1925 edition, Page 71:

The bronze portrait medallion of Mr. Paton was officially presented to the school on February 20th, on behalf of the Old Mancunians Association by the President, Mr. Miller. In the absence of Sir Arthur Haworth (Chairman of the Governors), Colonel Westmacott accepted it as a fitting tribute to one who had given so much of himself to the service of the School. In becoming, as High Master, "custodian" of the portrait, Mr. Miller said that although Mr. Paton's memory was deeply engraved in the hearts of all those who knew him, we welcomed a visible memento such as Mr. Cassidy's medallion, which would be a source of inspiration to future generations.

Notes: Frederick Hibbert Westmacott (1867 - 1935) was a Manchester-based surgeon, who had been educated at Manchester Grammar School and served with distinction in World War I. He lived at 21 Ladybarn Road, Fallowfield and was a member of the Board of Governors of the School. Sir Arthur Adlington Haworth, 1st Baronet (1865 - 1944), the Chairman of the Board of Governors, was a wealthy cotton merchant who lived in Altrincham. He was educated at Rugby School, not Manchester Grammar School, but was a prominent Manchester citizen, having served as a local Member of Parliament for South Manchester.