Supplement to the

Ernest Marriott page

Editor's note: while

researching Cassidy's statuette of Ernest Marriott, we came across this

essay by Marriott on the Internet Archive, embedded in the Papers of

the Manchester Literary Club. As a tribute to Marriott, and indeed, to

the the good people of Volendam and Marken, we re-publish it here in a

simple web-page form. - Charlie

Hulme, April 2009

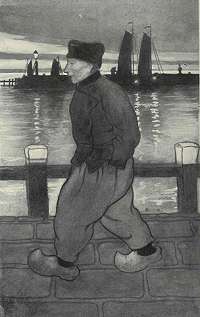

A Volendam fisherman Illustration by Ernest Marriott which

accompanies the original essay.

On the Ijsselmeer

A great deal has changed since Marriott wrote this amusing travelogue: Marken and Volendam are still picturesque, but now 'sight-seers' flock to them, often as a part of their short break in Amsterdam.

What remains of the Zuider Zee is now a lake, and is called the Ijsselmeer, having been closed off from the sea by dykes. Marken is no longer an island, being connected to the mainland by a land bridge.

The steam trams, almost new at the time of Marriott's visit, no longer ply the roads of North-Holland, replaced by buses, although a similar line south of Rotterdam line has been restored and keeps the memory alive.

Some modern links about the Zuider Zee:

Volendam Tourism

Marken Tourism

Rotterdam Tramway Museum, Ouddorp

ON THE ZUIDER ZEE

by

ERNEST MARRIOTT

(1907)

On the shores of the large gulf which, since its origin by inundation seven hundred years ago has been known as the Zuider Zee, the march of fashion is unheeded, and in the red roofed villages which cluster round the marge of this inland sea the transfiguring hand of modernity has been stayed. That a race of people should be wearing the same style of dress as that of their ancestors of three centuries ago is sufficiently remarkable. But that such a delightful state of things should exist so near to a civilisation of progressive vulgarity is still more so. In Holland the ancient and the modern rub shoulders, jostle against each other and drift apart again. The streams meet and flow along together yet do not mix.

This is one of the great characteristics that fascinate the observer. For instance, you may go to Scheveningen on the sea coast, a place of glittering sands and gigantic hotels and you will find the same characteristic there. Scheveningen is a Dutch Brighton with an immense stretch of promenade backed by fashionable café restaurants where the visitor pays four or five shillings for the privilege of eating an omelette. Yet a little way beyond the south end of the promenade, there is a tiny wooden-hutted fishing village that smells to heaven. In the clear summer evenings after the fishers have returned, to harbour the inhabitants, clad in their quaint baggy costumes and barbaric ornaments, sally forth out of the fishy reek and the tarry odour and walk along the electrically lit promenade into the fashionable throng. All seem to partake of the light and the glamour with equal zest. Yet the two classes are as far apart in their appearance and mode of life as it is possible for them to be.

It is extraordinary, considering the small area of Holland, how many varieties of costume are in vogue among the peasantry. Each colony has an individuality. Katwyk with its fishermen in scarlet bags, Volendam with its reds and dark browns, and Marken in a riot of green, vermilion and yellow are a few instances, while in some of the little known parts of Friesland the inhabitants resemble the nondescript pirate chief beloved by the patrons of burlesque melodrama.

Holland is small but fascinating. The tides of history surging through the centuries have not obliterated wholly the evidences of its early struggles as everywhere are traces and spoils of the past left stranded like bits of wreckage yet retaining an aura about them which conjures up to the mind a moving and inspiriting story.

The names of Dutch things are a joy though occasionally a trial. What could be more descriptive than the word "Klompen," which means clogs, or more tender than the word "Kinderen," for children ? As a counterblast there is the village of Alblasserdam surrounded by towns and hamlets, most of whose names have the same termination. Just as "Penelope" in Ireland, after seeing Ballyshannon, suggested a tour to all the "Bally" places, so might be suggested a visit to all the "dam" places in Holland, a start being made from a fairly well-known hotel in Amsterdam whose full postal address looks like a picturesque arrangement of profanities. Holland is, undoubtedly, the country of the "dammed." It is the land where you may obtain, what Punch calls, "satisfaction without profanity."

It was my second visit to the country of dykes and windmills. On the previous occasion I had been to the larger towns and had not time to see Volendam and Marken, the two places around which this account is written. The way thither involves several changes. The train from the Hook reached Amsterdam at 9 o'clock in the morning and after breakfast I went down to the harbour and booked my passage to Volendam. The journey is in three stages. First of all you board a tiny steamer which is called, for short, a "Havenstoombootdienst," and, if you are unlucky as I was, you will be the only male passenger, the boat usually being crowded with Zuider Zee fisher-girls going back to their homes after an early morning visit to the City. It was a somewhat trying experience, though it might have been worse had I understood the language they were speaking. There are a number of bridges under which the boat has to pass, and some of them are so low that it is necessary for the passengers to duck down as the steamer without pausing glides underneath. Strangers in the land are considered fair game for a Dutch joke, and, no warning being given, the unwary foreigner will contribute to the gaiety of Holland by leaving a portion of his head adhering to one of its bridges. Luckily for myself I had been on the canals before, and when at the psychological moment I ducked my head, I was amused to see that a number of the girls had become so excited in the anticipatory enjoyment of an excruciating humorosity that they did not look out for themselves. I was not to blame for what happened, but from the looks I received one might have imagined that I was the blackest criminal alive.

After more "duckings" we landed, and began the second stage of the journey by a steam tram with a wheezy boiler-contrivance pulling four carriages after it. The route lies through the open country and after three hours jolting it becomes slightly monotonous. The engine continually loses its puff which means that the male passengers get out and smoke while it gets its breath back. We pass through wide green pastures dotted with solemn-eyed cows and bedecked with gesticulating windmills, the track running on the edges of the roads and along the willow tufted banks of the canals. When a village is reached the tram slows down to a crawl, the guard gets off and walks in front of the engine down the main street clanging a big bell. The entire population turns out to watch our passing, It is the event of the day. At every window and door are peering faces, and on each side we are escorted by an extraordinary number of small children in clattering sabots. These villages are wonderfully clean and bright. Each house is different in style and colour from its neighbour, and under an intense sunlight the effect is dazzling. At every stopping-place the number of passengers lessened, and I was the only one left when the tram came to the end of its journey at Edam. Here my luggage was taken up by a taciturn individual in a marvellous patchwork coat who beckoned me to follow him. It was a hot day with a blistering sun and after walking down many shining streets we finally came to a weed-covered waterway with a little cove under a clump of trees. He plumped my bag into an old worm-eaten sailing boat and indicated in three solemn and expressive gestures that somebody would come along presently and convey me and my baggage along the canals to Volendam. He then wandered away.

Time is of no account on the Zuider Zee; nobody ever thinks of worrying about anything, therefore, I got out of the quivering sunlight and into the boat and sat smoking in the green gloom for half an hour until a fat youth encased in balloon-like trousers drifted slowly on board. He wore a rapt and ecstatic smile which widened alarmingly when I offered him a cigar. After lighting his smoke from mine he displayed a little energy and hoisted a sail. Then began the last stage of the journey and in more time than it would take to walk we drew quietly into Volendam, the region of strange odours.

Volendam dates back to the fourteenth century. It is underneath the level of the sea and nestles close by the protecting dyke, the top of which is used as the main street. Asyou step on to it you annihilate time, as it were, and spring back a few hundred years. In one stride you are back in the past. A first impression has a dreamlike quality. The narrow streets with their rows of tiny wooden huts with pointed gables suggest a colony of dolls houses. The fishermen, giant-like, bronzed and imperturbable, are clad in fur hats, magenta jackets and the baggiest of baggy breeches made from a material closely resembling in appearance and texture the felting used for the roofing of hen-coops. The apparent unreality of things is enhanced by their behaviour. Here there is no "'eaving of 'arf bricks" at the stranger. Instead, the traveller finds himself taken for granted. Without even a glance of curiosity he is accepted as part of the cosmos. As I saw these big fellows kick off their wooden klompen outside their doors and stoop to get inside their houses, it suggested to my fancy the men of Brobdingnag attempting to live in Lilliput.

I was to stay at the Cafe Spaander which is the only hotel in the village. It is a delightful little inn built mostly of wood and resting on piles at the edge of the dyke. The charm of the place is incommunicable by mere words. On the threshold the expected visitor receives a welcome so hearty that he is almost bewildered and wonders whether he has been mistaken for a long lost relative. And the warmth of the greeting is only equalled by the sorrow at his departure. Moreover he will realise before a week is out that this friendliness is sincere and genuine. The cafe is and might well be famous. There were about twenty-five visitors of various nationalities staying there when I visited it. Most of them were strangers to each other, but we all became united in the brotherhood of Art. Volendam happily has no attraction for the ordinary sight-seer as the only accommodation is at the Cafe Spaander where, a visitor who betrayed no inclination to paint or sketch would feel himself to be a sort of pariah and would be regarded with grave suspicion.

"Of course you have come to paint, Mr. So and So? " No? Then you draw with the pen or pencil ? No ? Ah ! Then you must have come with a camera to take photographs ? NO ?" Blank astonishment and confusion ensues. Outraged artists attack in a body and stab the intruder to death with palette knives and portcrayons.

It is a fact that a few years ago a famous painter was actually refused lodging there until he produced his sketch book. Many well-known artists have stayed at the cafe and most of them have presented a painting or drawing to the proprietor. The wooden walls of the long low rooms are covered with them. There are paintings by Stanhope Forbes, Moffat Lindner, Cassiers, Josef Israels, and many others. The lighter side is represented by Phil May, Tom Browne, and Will Owen, who have contributed many amusing sketches. Thecollection has now attained some importance and must be worth a considerable sum.

It is pleasant to think over the happy days spent in this antique village; rambling about on the cobbled edges of the canals seeking subjects for sketches, lying on the grassy slope of the landward side of the dyke smoking aromatical cigars at two a penny who could help being a philosopher with cigars so good and cheap working at a drawing in the shade of the hut where klompen are sold in strings like onions, with the model blinking in the sun and looking contemplatively happy at the prospect of earning fivepence an hour. In the evening walking along the top of the dyke, with the waves of the Zuider Zee gently lapping the seaward slope, while down below on the other side could be seen the Yolendam milk maids with their white-winged, caps glimmering in the dusk bringing the cattle home to the sheds. And later on to get to the end of the wooden jetty and look back at Volendam sleeping in the starry silence. The lights from the inn stain the water with gleaming coloured shapes. Away to the right the moon splashes the sea with silver, against which an arm of the harbour stands out intensely black as if painted with indian ink, while the sailors' beacon at the end of the quay communicates to the water one wriggling worm-like reflection. And then the nights spent in the cafe itself. The hotel is built on the edge of the dyke near to the harbour, and after dinner we sat out on the broad wooden verandah with our coffee, watching the fishing smacks gliding home through the grey-green water, while the last rays from the setting sun fired their brown sails to glowing orange and lit up the tops of the worm-eaten harbour piles as with a yellow torchlight. The boats would sometimes pass so close to us that we could hear the steady snore of the water under their bows and, as they neared the harbour entrance, they would slip one behind another and resolve themselves into a stately procession, each vessel carrying a silent and statuesque figure at the helm. Later on a big white moon would float up into the heavens and flood everything with radiance. Inside, the tavern was bright and shining with cleanliness, and when it got too chilly for us to sit outside we continued the evening in the long low bar-room which is the main apartment of the Cafe Spaander. This room has a boarded floor which through continuous scrubbing has become bleached almost white. Scattered about are small mahogany tables, and at one end is a piano standing near some brackets which are holding beautiful models of ships. Oil paintings, charcoal sketches and water colour drawings in great variety convert the room into a miniature picture gallery. It was here that we spent most of our nights. A mixed company, with a bond of fellowship, we never found the evenings too long. A few would play billiards, one would tinkle on the piano, there would be a group playing cards, and other groups chatting away unconscious of the fact that the little French artist was making ludicrous caricatures of them in his sketch book. We smoked continuously until the features of the room became somewhat indistinct in the blue haze. Every one was contented and seemed to catch the infectious happiness which emanated from the host and hostess and their charming daughters, who were interspersed among the visitors helping to make things go. Towards 11 o'clock, when the company had thinned down, about a dosen of us, including "Old Spaander," would gather round a table with our smokes and liquids and yarn away till midnight, when the host would solemnly and fervently wring each of us by the hand and express the hope that we would sleep soundly.

About the middle of the week a fisherman took me over to Marken in his sailing boat. Marken is a small island whose early history is unknown. Once the property of the Monastery of the White Friars and afterwards the haunt of pirates it has continually waged war against the sea and succeeded in keeping its head fairly dry underneath the sea level. It is completely surrounded by a strong sea-wall which is not always strong enough and has been kept under suspicion for centuries. Even now it is not safe, the island is often under water and the inhabitants made captive on the mounds on which their settlements are built. Marken is not big, you can walk round it in three or four hours. But the Markeners are bigger even than the Volendamers. They are a distinctive race, entirely original in their manners and appearance. How they got there and from whence they came nobody knows. There is a suggestion of the Laplander about them. The villages are built on wooden piles or mounds of earth and are separated from one another by about half a mile, and in the centre of the island is a big grass-covered mound. This is the burial ground, the reason of its height being apparent when you are told that the winter tides break down the weaker portions of the dyke and burst in flood over the lower levels.

I had arranged with the fisherman the night before to sail me over, but when I awoke and looked out of the window the sea was grey and cruel looking and there was a strong wind blowing high and sonorous with a sound like that which is heard in a ship's rigging. I thought the visit would have to be put off but the gale, however, died down, the sun came out before we started, and there seemed every promise of a fine day. "We arrived about 11 o'clock in the morning. It was blazing hot when we got there, and x the fisherwomen in their vivid embroidered costumes looked exceedingly gay as they walked about the harbour. The prevailing colours they wear are vermilion, yellow and green, and nearly all of them have tow-coloured hair. It was a gorgeous sight. They seemed to have burgeoned out into tropical flowers.

On the island itself the predominating colour is green. All shades are to be found on the houses; olive green, bottle green, pea green, and apple green, and where the paint has been left long to the action of the sun and salt air it has turned to brilliant verdigris. The contrast for which the eye seeks is supplied by the clothing of the inhabitants and the great red roof-tiles which are curved like those of a pagoda.

The sun poured on everything with intense brilliance and the pitch on the lower boards of the huts seemed to sputter in the burning glare. I rambled about for an hour or two and after visiting four of the settlements was glad to rest in the quiet pool of shadow made by the little church and consider the greenness of the Marken land and the exceeding great flatness thereof. Dutch weather is as uncertain as our own. A faint breeze sprang up bringing dark-looking cloiuds which distributed the sun- light into moving irregular patches. I rose to go and, turning a corner, stumbled upon a funeral. It brought me to a standstill for it was not like an ordinary one.

The first thing that struck me was the entire absence of morbid interest on the part of the neighbours. Neither was their any ostentatious display of grief from the mourners. There were six bearers who had just hoisted the coffin on to their shoulders as I caught sight of them, and they seemed to be awaiting some signal. A bell began to toll from the burial mound, and at the second stroke the procession started with the priest walking in front. The coffin had a plain black pall draped over it, and following behind were a number of fisher-girls in plain black and white. The simplest things are very often the greatest.

This was exemplified here. The vulgar trappings of woe which usually accompany a funeral were absent and in their place was simplicity and sincerity. As the procession moved slowly and steadily by the weedy waterways, the sky grew darker with impending storm and, by a strange freak, the heavy thunder-blue clouds were urged along in the same direction and apparently at the same pace. The bell ceased tolling when the cemetery was reached, and almost immediately the sky began to crackle like musketry. I could not see plainly from my shelter owing to the rain which now began to descend in torrents. The remainder of the ceremony was seen indistinctly, and the thunder became more frequent and punctuated by flashes of lightning. An immense gloom had descended on everything, intensified by the sudden pallid flares and bursts of sound. Nature was giving to the dead fisherman a magnificent requiem, and it seemed to invest him with an immense and portentous dignity. The ceremony on the mound went on without signs of hurry, and towards its conclusion the storm began to abate, and ragged strips of lemon-coloured light broke through the clouds. The gloom rapidly lifted and as the burial party returned the downpour ceased, the sounds of the storm, died away into distant mutterings, and the sun shone out again on the glistening roofs. The warm rays danced every where flashing from rills and pools, and setting the wet grass all a-twinkle till the little island became like a big green jewel shimmering in the sea. As I made my way to the harbour a venerable stork with long red legs flapped from out the remains of a wrecked boat whose gaunt ribs stuck out of the grass like the bones of some long deceased monster, and winged its way over the house tops.

Before returning to Volendam I had a look into some of the Marken houses. They are all more or less alike with their Delft tiles, ancient pottery, old oak and shining brass-ware, but they are all beautiful. The gods be thanked! the Markeners are not yet "civilised." They know nought of the cult of the antimacassar nor do they establish as an article of decoration in their homes, the lone bulrush in the painted drainpipe.

One of the remaining days I spent at Broek which has the reputation of being the cleanest village on earth. Here are to be found the trimmest and most formal of gardens, shippons with curtains to the windows and strips of carpet on the floor of the stables. Round its name has gathered wondrous tales to the effect that the inhabitants prefer to live on raw food rather than soil their cooking utensils, and that boys are employed to blow the dust out of the cracks between the paving stones every half hour during the day. Space will not admit of a description of the famous " dead " towns with their grass-grown streets and dilapidated houses mute with the poetry that accompanies architectural decay, nor of the romantic origin of the Zuider Zee with its half forgotten legends of buried cities sleeping beneath its waters.

Many impressions crowd in great variety upon the mind but among those which have been described are the two that appear most vividly to the memory the grey-green evening sea at Volendam with the sunset fire on the sails of the fishing boats and the burial of the fisherman on Marken island in the midst of the thunder and lightning and the sweeping curtains of rain.

Edited by Charlie Hulme from Manchester Literary Club Transactions Volume 33, being a reprint of pages 95-106 of Vol.36 (1907) of The Manchester Quarterly : A Journal of Literature and Art. From a copy in the Internet Archive.

Page created April 2007.