This site celebrates the life and work of sculptor

John Cassidy (1860 - 1939).

Editorial.

[from the Manchester University Magazine, Vol. X. No.6,

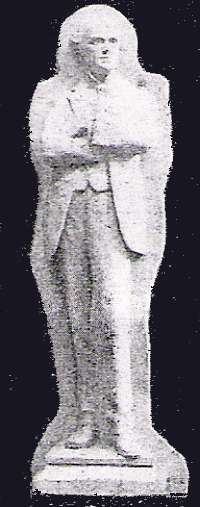

March 26 1914.]We print to-day an article by Mr. John Cassidy on "The Making of a Statue." Apart from the interest which attaches to a description of his craft by a master, we are fortunate in that the article is illustrated by photographs of a statuette of Sir Alfred Hopkinson, recently executed by Mr. Cassidy. Anyone who has been to the Spring Exhibition at the City Art Gallery will have seen this statuette, and perhaps we could point to no better example of Mr. Cassidy's mastery of the difficult art of portraiture. He has recently been elected a member of the Royal Society of British Sculptors, and is exhibiting two pieces of work at the Paris Salon this year - one of which is the exquisite study of the late Captain Scott and his followers on their way to the South Pole, which was shown last autumn at the City Art Gallery.

Notes:

From the general style, the article would seem to be based on a lecture which Cassidy is known to have gave given to various institutions and societies. For example, on 10 March 1880, the the history of Manchester Free Libraries records:

In 1890, three lectures were

delivered in the Reference Library by way of experiment.

On January 13th, Mr. Alfred Darbyshire lectured on

"Secular Architecture" ; on February 10th, Mr. Percy S.

Worthington, B.A., discoursed on "Ecclesiastical

Architecture," and on March 10th, Mr. John Cassidy spoke

on "Sculpture," giving during his discourse practical

illustrations in the art of modelling in clay. A list of

the more important works contained in the library relative

to the subjects expounded was printed on the

syllabus of each of the lectures. The room was crowded

with attentive and appreciative audiences.

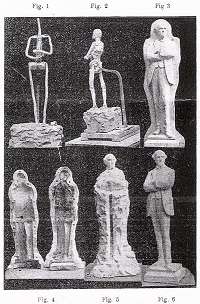

The text of the article as printed appears to have been condensed by Cassidy himself or the editor: the illustration has five pictures, Figs. 1 to 6, but only the first two are referenced in the article.

Ghosts

The trial referred to by Cassidy took place in London in 1882. Charles Bennett Lawes had publicly, in an article in Vanity Fair magazine, accused fellow sculptor Richard Claude Belt of using a 'ghost' - passing off as his own works which had actually been done by Thomas Brock or Mr Verhyden.

Lawes lost the case, and was ordered to pay £5000 damages to Belt. He appealed, and lost again in 1884, but which time he owed over £10,000 in damages and costs, and was forced to declare himself bankrupt.

However, in 1900, on the death of his father, Sir John Bennet Lawes, he inherited the Baronetcy and family fortune, including the Rothamsted Experimental Station that his father, a famous horticulturist, had established, and which still flourishes a century later. He died in 1911.

For a fuller account of the trial and the events surrounding it, see Wikibooks: The Rowers of Vanity Fair and John Sankey:

'The sculptor's ghost – the case of Belt v. Lawes.' Sculpture Journal v.16 no.2, p. 84-89, 2007.

Vital Energy

The work by George Frederick Watts (1817-1904), completed in 1903, and referred to by Cassidy as 'Vital Energy' has, like many sculptures, been given various names over the years: the most accepted version, believed to have been used by Watts himself, is 'Physical Energy'.

Three casts were made: the one for the Rhodes memorial in Cape Town, mentioned in the text, one now in Harare, Zimbabwe and one now in Kensington Gardens, London, seen here as photographed in 2009. The original plaster model also still exists, in the Watts Gallery in Compton, Surrey.

Watts abandoned clay modelling adopted the direct plaster working in his later years when he suffered from rheumatism, according to David Loshak: 'The mind behind Physical Energy' Konsthistorisk Tidskrift/Journal of Art History 37: 2, 115 — 130, 1968.

Fig.3 from the article, enlarged, showing the plaster mould made from the original clay model.

THE MAKING OF A STATUE

By John Cassidy, R.C.A.

It seems at the outset somewhat irreverent for me to attempt to describe how statues are made, when we remember that the subject comprises the countless masterpieces of all ages, some of them reaching back to 4,000 years ago and further; creations which, at this distance of time, have grown rather than lessened in importance, and have rendered famous the memory of the nations that conceived them and the age that gave them birth. To explain the mystery of these choice productions, and how they were made, would be an impossible task; but there is one important truth underlying all sculpture worthy of the name and that is, that the means employed by the sculptors of old to represent the ideas current at their time were pretty much the same as those employed by us to-day.

However much the ideas themselves may vary, however changed may be the natural characteristics of race, of creed, of social or political conditions as shewn in that sculpture, the sculptor's language - "the representation of form as the exponent of life" - was the same then as it is now; he had to appeal to the same sense of beauty, the same understanding of form, to the same appreciation of line, curve, and composition. What was beautiful four thousand years ago is judged now by similar and equally sensitive eyes, and so far as the objective side of the work is concerned, is equally understood and appreciated.

Sculpture may be defined as the converting of any shapeless mass of solid or pliable matter into some form of life, which may be either human, animal or from vegetation. Thus it is nature that is called upon to supply the means by which the sculptor seeks to attain his end. This is true even of highly emotional but uncultivated races, such as the Indian, who expressed their religious ideas in sculpture by carving the bodies of their Gods with numerous arms and several heads. These abnormal productions are nevertheless based on nature, and are but the exaggeration of natural forms due to an unbalanced imagination in the race.

We may assume, then, that a sculptor looks to nature as the storehouse that must supply his forms; all he has to do is to read just and adapt them artistically. Art is nature seen through the mind of man, and it is in this process of translation that all the possibilities, all the realisation of wonder and beauty, lie. Thus the first care of the sculptor is to master the idea that he wishes to express, to select his form, and then to set about interpreting it into some durable material.

A child, with its strong imitative faculty, will eagerly take clay, if it is within its reach, as a means by which it can copy some object that it has seen, because it binds well together, and if the object is solidly constructed will remain without supports when completed. The expression "mud pie" is a very applicable one, not because children invariably make pies of mud, but because they can be made without a frame work; so can apples, pears, plums - in fact any kind of fruit or detached forms.

It is in this simple material, and because of its perfect plastic qualities, that a sculptor, as a rule, first works out his ideas, though at times he uses wax for smaller sketches, to save the expense of casting or getting the clay fired. I may here say that in sculpture it is much easier to make a creditable beginning than it is in the sister art of painting. Given material, some form can be directly made out of it without much effort of interpretation or knowledge of the art of rendering, whereas, in painting, or even in drawing, a certain ready imagination as well as knowledge is necessary, in order to make a solid object look solid on a flat surface.

If we sculptors do not bake our clay sketches we cast them for preservation, for the purpose of copying them into marble or bronze later on. The question of size, pose, and treatment of a statue is much affected by the ultimate destination of the work. For what would look well in one place would not suit another. A sculptor has many things to consider in this way. A statue may appear, and in fact may actually be perfect in proportions, and look all right in his studio, but when it is erected on a high pedestal and placed in the open air, it may show many defects. In all large statues and groups which are intended for the open air certain exaggerations must be made. If a statue is an absolute copy of a human figure it will be a failure as a work of art. The great difficulty of a sculptor is to feel how much detail should be left out, and how much exaggeration put in to get the desired effect. Let us take a statue, say fourteen feet high. In a work of this size the exaggeration I refer to should be in the head and shoulders. Unless this is done the statue will appear to be too small about the upper parts. The head and shoulders, being the farthest from the eye, naturally diminish to our sight. When I was a student I remember reading an account of a bronze statue that was erected in the South of France. It was of a local poet holding a large open book. It was only after the bronze was cast and erected on its pedestal that it was discovered that the poet's head was hidden behind the book. Now this model, no doubt, would have appeared to look all right in the sculptor's studio, especially if it were modelled on a low stool. The sculptor felt so aggrieved over his mistake that he ended his life shortly after.

Further, not only the preliminary idea, but also the after effects, have to be carefully considered and fittingly worked out. Broadly speaking, a sculptor's subject is not his own; but he renders the prevailing ideas of the age in which he lives. The Assyrian and Egyptian expressed the despotism' of their times, the Indian and Greek their religions, the one based upon super-naturalism and the other upon nature; modern Europe expresses the passion for national glory. The sculptures of the past have been of untold value to the historian in tracing the "Time Spirit" through the ages, just as geology has revealed the history of the material universe. But, speaking less philosophically, the sculptor has a great deal to do with the choice of his subject, and in that choice his own taste and individuality must assert themselves. Sometimes the chance action of a figure suggests an idea, a passage in his reading, a tale that has thrilled him from boyhood, or a character that he has specially loved. But as often as not he is commissioned to work out some given idea, and even the lines on which he is to work are fixed for him. Even then there is ample scope for his own skill in working on his material.

Sculptors differ as to the way in which they set out to work a design for a group of figures, or even to make a portrait; some make drawings as a preliminary. For myself, I can express my thoughts more readily when I have the clay in my fingers, and am better able to realise the effect of light and shade than I could by making a drawing; in fact, I can get a better portrait in one hour's sitting by using clay than I could in eight hours by making a drawing in light and shade. It may be accepted as a general rule that all statues, whether intended for bronze, marble or stone, are first of all modelled in clay. The reason for this is obvious. In clay the result is so much more quickly attained, and the work, even when nearly finished, can be readily altered by either putting on or taking off. It is also a cheap method, since the clay can be used again and again. It is possible, nevertheless, to carve direct in the stone. It has been done in past ages, but the usual and safer way is to make a model first. Let us suppose it is a figure in the round upon which a sculptor is about to start. The first thing he does is to build up a skeleton or framework (see fig. 1), guided by his sketch as to proportions and general requirements. The framework is a matter of great importance, for if not made strong and capable, the model will collapse. The skeleton work is made of iron bars, the strength of which is regulated by the size of the statue. Clay, as you know, is a heavy material, and two tons will be needed for the making of a model of a ten-feet figure.

When the framework has been securely built up, making due allowance tor the possibility of altering or adapting as the work proceeds, the modelling commences. This merely consists of laying on clay where it is wanted, taking care that it adheres to the supports as it is pressed on. The skeleton of the human figure is first of all aimed at, fixing the position of the top of the head, the clavicle, or pit of the neck, the width of shoulders, the pelvis, or hip bones, the knees, and so on (see fig. 2). Then the muscles are laid on, and so one advances from one stage to another until the figure is complete in the nude state. Whether the figure is to be eventually draped or not, it should always be modelled in the nude. This is done to make sure of the action and proportions. There are, of course, deviations from the method described, and in those deviations the character of the work and also the individuality of the sculptor asserts themselves.

The varying methods employed can be detected in the result, for naturally one aspect of the art appeals more strongly to one sculptor, another aspect to another, and each will work in the readiest way to achieve his particular end in view. For instance, some sculptors with a colossal work in hand would make a highly finished model on a small scale, which is afterwards measured up and enlarged by skilled workmen to a required size, and only finally touched up by the master hand; others make merely a rough sketch at first, and then build up, developing the large clay model, altering at will as they go, until eventually it may have very little likeness to its diminutive predecessor. Again, some sculptors merely work at the full-sized model just enough to ensure sufficient material being left for the "pointer" to transfer the rough form to the stone, leaving all detail and expression to be carved once for all in the final material. This, however, only applies to architectural figures; it would not do for a portrait statue.

Sometimes, though very rarely, a sculptor models direct in the plaster, but only in colossal work. I had the pleasure of seeing the late G. F. Watts work upon his "Vital Energy" group, the bronze of which now adorns the grave of Cecil Rhodes. He made his model direct with tow [flax, hemp, or jute fibre] mixed in the plaster. It would have been impossible for him to have used clay as he did the work out of doors; clay would have dried and fallen to pieces in a very short time, whereas this model stood in his garden for eighteen years before he finished it. Plaster is not only unpleasant and sloppy to handle, but very inconvenient, since it sets in a few minutes and half one's time is spent in mixing the small quantities which can be used before it solidifies.

A great many of the statues and busts executed nowadays are posthumous, so that the sculptor cannot model them from the life. It happens, in some cases, masks have been taken from the deceased, but otherwise photographs alone are the source from which a likeness can be derived. A cast from death is useful, but by no means indispensable. indeed, sometimes it is worse than useless, as in the case of children and youth generally, where everything that distinguishes youth - the rotundity of form, the delicate subtlety of line, is missing in the dead mask, and the formation of the bones of the head is all that can be relied upon. There are many people under the impression that a sculptor takes a mould of his sitter's face. I met one of these a few years ago. He was a town councillor, by the way. He was a very prompt business man, and had a great reputation for punctuality. I wondered at the time how he had acquired it, for he kept making fresh appointments with me from one week to another. But eventually he did turn up one morning looking very glum, with his beard cropped very short, and the shaggy eyebrows, which I pictured in my mind would be telling in effect, completely gone. He looked quite a different man; but as his state of humour did not encourage me to be inquisitive, or personal, in my remarks, I asked him to take a seat on the throne, and commenced to talk about the weather, and so on. Whilst I was laying pieces of clay over the rough model which I had prepared, he watched me in silence for some time, until he saw me form his nose. Then I saw a brightness beam over his face. "Oh! is that how you do it?" he remarked in a delighted voice. I said "Yes; what other way did you think I did it?" "Well," said he, "what a d--- fool I must be. I thought that you poured plaster over my face, and so did the missus, for she made me cut my beard and my eyebrows, too, in case you couldn't get the plaster off."

However, as a matter of fact, there are isolated cases where this is done. When having the sittings for the bust of the late Cardinal Vaughan, he told me that he had gone through the ordeal of lying on his back with quills inserted in his nose, wherewith to breathe through, whilst a moulder oiled his face and afterwards poured a basin of plaster, mixed with tepid water, all over his mask. He had to keep rigidly still for quite three minutes until the mould set. The reason why he consented to this was to save the time of sitting; he was in Rome then and had to return to England next day. It is a curious fact that a mask cast from life in this way has very little of a portrait in it when compared with one that is modelled. I think this is due to the weight of the plaster pressing upon the fleshy parts, or perhaps it is because of the hard expression of the face under such unnatural conditions.

Sculptors, as a rule, treat their clients more mercifully than do their brother painters. In the first place, they do not want so many sittings. It is no uncommon thing for a painter to exact twenty or twenty-five sittings for a portrait. Watts told me that he had as many as forty-eight sittings from Cardinal Newman for his portrait. This portrait is now at the Tate Gallery, and is decidedly the finest portrait of the 19th century. In justice to Watts, I may say that although he had so many sittings for this portrait, he has painted portraits of Foreign Ambassadors at one sitting. One advantage a sculptor's sitter has over a painter's is that he can move about and has not to look always in one direction, at least when sitting for a bust or figure. For a medallion we have to be just as exacting as our brother painters, and require a fixed pose.

For subject work and for portrait statues models, male and female, are indispensable. Portrait statues, like busts, are, as I have said before, generally executed after death, but even if executed in a man's lifetime, he seldom has the time or inclination to sit for more than the head. I will not say that the work does not therefore suffer in some degree, for as much of the man's individuality depends upon his figure as upon his face, and this no one can represent but himself. Be this as it may, it is seldom done, though I have an instance of a client calling unexpectedly one day when I had a model doing duty for the legs of his statuette; he there and then resolutely decided to stand for his own legs. But this is a notable exception.

As well as models, there are other assistants indispensable to a sculptor. First of all there is the casting of his clay models; this gives use to the trade of the moulders, several of whom in London alone have, with their assistants, constant employment. Then there are the bronze founders, who depend largely for their business upon the work from the sculptor's studio. Again, the "pointers" already referred to are indispensable, whose business is entirely created by the needs of a sculptor. Besides these, there are the more skilled assistants, who are required at times, both in modelling and carving, though their employment varies, not only according to the amount of work in the studio, but also according to the individual characteristics of the sculptor. Some require little or no assistance in modelling, others much. Some never touch the marble at all, while others are very particular that all the finishing shall be by their own hands.

Some thirty years ago, during a memorable trial in London, much was said and made of the sculptors' "ghosts" - men who were supposed secretly to do the work instead of the so-called sculptor. Secrecy apart, it is often difficult to say how far assistance is legitimate, or how far it is the mere trading upon others people's abilities, and therefore unjustifiable. Assistance to a sculptor who has work to do beyond a certain quantity, and which often must be finished at a given time, is indispensable, and, provided that the sculptor is unable to do all the work himself, it is a matter of expediency or choice, to what he devotes himself, and what he gives to assistants. He ought, naturally, to make his design or sketch model, and decide upon the form his work should take. Many of the important sculptors, in the art cities, select their assistants from the younger men who are studying at the schools or academies, thus affording them the opportunities for learning the practical side. There is no better school for the student than the studio itself; and although the practice of apprenticeship has died out from this as from other professions, yet the spirit of it is thus kept alive in art, and the hope of the future lies in the traditions of the studio being carried on from one generation to another.

Transcription by Charlie Hulme, August 2010. Special thanks to Janet Wallwork of the John Rylands University Library, Manchester, for discovering and providing the original.