| This site celebrates the life and work of sculptor John Cassidy (1860 - 1939). |

Sir Alfred Hopkinson (1851 - 1939), subject of a bust and a statuette by John Cassidy on the occasion of his Knighthood in 1910, was a notable member of a remarkable Manchester family. The biographical sketches on this page cover just a selection of its members over three generations, but hopefully provide a flavour of their achievements.

The Hopkinson Clan

In the words of Roger Chorley, husband of Sir Alfred's niece

Katharine, in an introduction to her book Manchester Made Them:

'When eventually they died he sought her hand, but being proud, she refused. It is a nice legend but the truth is probably more prosaic - that he had already made an unfortunate marriage in South America. We shall never know. Either way, there is little doubt that Alice was a quite considerable person. She had one son, John, and four daughters, one of whom married H.O. Wills of the Bristol tobacco family.'

Manchester-born John Hopkinson (1824-1902) served an apprenticeship as a millwright with the firm of Wren and Bennett in Manchester, rising to become a partner in the firm, which became Wren and Hopkinson, whose works was on Altrincham Street on what is now part of the University (ex-UMIST) campus.

In 1848 he married Alice Dewhurst, born in Skipton, daughter of John Dewhurst the head of the Dewhurst cotton spinning firm, where Wren and Bennett were installing machinery. The couple lived in Skipton with the Dewhursts for a while before moving to Manchester.

He left in 1881 to become a self-employed consultant; he also served as chairman. In the course of his career he installed cotton-mill machinery in many mills in Britain and around Europe.

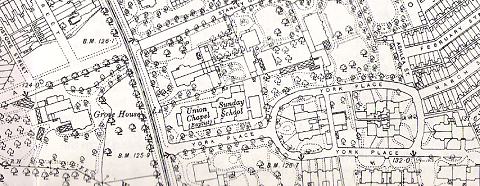

By 1861, when John senior was elected councillor for his local Ward, St Luke's, the family home were living in a large house, 12 York Place in a secluded private development in Chorlton-on Medlock, off the Oxford Road, where they remained in 1871: John and Alice with their children John, Alfred, Ellen, Charles, Mary, Edward, Elizabeth, Gertrude, Albert, Mabel and Henry (two children died in infancy) plus three female servants: Elizabeth Philips, Mary Rigg and Mary Fletcher. In 1872 he was made an Alderman, and served as Mayor in 1882-3. The family moved across the Oxford Road to an imposing Georgian mansion, Grove House, with a large garden which required a live-in gardener.

The 1880s saw John, like many of the city's wealthy businessmen of the era move his remaining family out of smoky Manchester to the green fields of Cheshire where they made their home at 'Inglewood', St. Margarets Road, Bowdon. In 1888 Grove House was sold to the executors of Sir Joseph Whitworth and became the core of the Whitworth Art Gallery (see the Rusholme Archives for pictures), its gardens absorbed into the Whitworth Park. As for York Place, it became gradually swallowed up by the development of the Manchester Royal Infirmary and St Mary's Hospital, and eventually disappeared from the map.

'Inglewood' is a Victorian mansion built for Alexander Ireland on land bought by him in 1869 from the Earl of Stamford's Dunham Massey estate. Alexander's son, classical music composer John Ireland, grew up there.

John Hopkinson senior died in 1902; his widow Alice continued to live at 'Inglewood' cared for by four servants and her unmarried daughter Mary. Katharine Chorley writes in her memoir Manchester Made Them of childhood visits to the house at this period: 'Granny sat with her back to the light on one side of the fire in the morning-room. The heavy curtains and furniture, the big table with its serge tablecloth...'

Alice died in 1910, and the house was sold by Alfred, Charles and Edward Hopkinson, executors of John's will, in 1911 for £1,775 to John Gill, a retired manufacturing chemist who had recently inherited and sold a house 'Clairville' in Kersal, from his uncle, retired textile merchant Robert Robinson. 'Inglewood' still exists - with the same name - in 2012, converted into flats and with a modern extension added on one side.

John's eldest son, also John Hopkinson, attended Lindow Grove, a Quaker-run school in Alderley Edge, Cheshire, then studied at Owens College and became an electrical engineer, initially working for his father before embarking on a career of his own. He became Professor of Electrical Engineering at King's College, London and acted as a consultant for many companies.

In 1877 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in recognition of his application of Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism to problems of electrostatic capacity and residual charge. Tragically, he was killed in an accident in 1898, along with three of his children, while climbing in Switzerland.

Edward Hopkinson (1860-1922) married Minnie Campbell of Belfast. Their daughter Katharine, under her married name of Katharine Chorley, wrote a marvellous book about her life and times in Edwardian Manchester, the Hopkinson family and her neighbours in Alderley Edge.

Edward, like his brother, was an electrical engineer, educated at Owens College and Emmanuel College, Cambridge. He was personal scientific assistant to Sir William Siemens, and therefore gained early practical experience of the electrification of railways, such as the line from Bessbrook to Newry, opened for traffic in 1885, and the City and South London underground line. He became the head of the electrical department of Manchester firm Mather and Platt, and later a partner, then managing director.

He was made a partner in the firm, and when it became a limited company, he became managing director, and later vice-chairman.

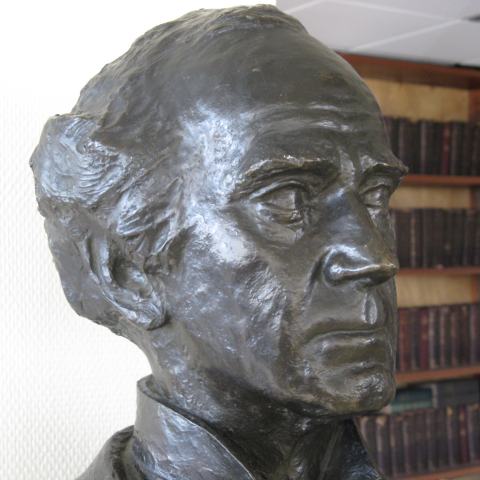

The Cassidy bust

The bust in the School of Law, 2012. The text on the wooden plinth reads:

ALFRED HOPKINSON

KNIGHT, K.C.

STUDENT OF

OWENS COLLEGE

1866

PROFESSOR OF LAW

1875

PRINCIPAL OF

OWENS COLLEGE

1898, AND

VICE-CHANCELLOR OF

THE VICTORIA

UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER

1903 - 1913

MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT

FOR THE

COMBINED UNIVERSITIES

1926-1929

KNIGHT, K.C.

STUDENT OF

OWENS COLLEGE

1866

PROFESSOR OF LAW

1875

PRINCIPAL OF

OWENS COLLEGE

1898, AND

VICE-CHANCELLOR OF

THE VICTORIA

UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER

1903 - 1913

MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT

FOR THE

COMBINED UNIVERSITIES

1926-1929

Links and references:

Alfred Hopkinson, Rebuilding Britain: A Survey of Problems of Reconstruction after the World War. London: Cassell, 1918. Full text available on Project Gutenberg.

Alfred Hopkinson, Penultima [a memoir]. London: Martin Hopkinson Ltd, 1930.

Alfred T. Davies, ‘Hopkinson, Sir Alfred (1851–1939)’,

rev. Catherine Pease-Watkin, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography,

Oxford University Press, 2004

Bertram Hopkinson, 'Memoir', in John Hopkinson [Junior], Original

Papers by the late John Hopkinson, vol.1, Cambridge

University Press, 1901. The

Internet Archive.

Whitworth

Park and Gallery, part of the Rusholme Archives.

Katharine Chorley [née Hopkinson], Manchester Made Them. First published in 1950 in text-only form by Faber and Faber. Re-issued with new introduction (by Roger Chorley) and many photographs by The Silk Press, Macclesfield 2001.

Gerald Hurst, Closed Chapters. Manchester University Press, 1942. (extracts available through Google Books)

Indenture of Conveyance, 'Inglewood', Hopkinson brothers to John Gill. Private collection.

Census and other records on www.ancestry.co.uk.

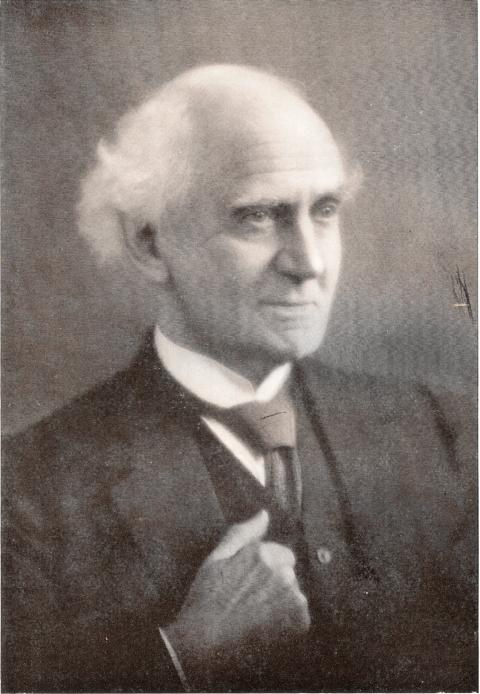

Sir Alfred Hopkinson (1910)

Alfred Hopkinson was born in Manchester on 28 June 1851. He was appointed Principal of Owens College, Manchester, in 1898, and remained in post, taking the title of Vice-Chancellor, as the college became part of the Victoria University, and after 1903 the Victoria University of Manchester. He was awarded a knighthood in 1910, the year Cassidy's portrait of him was modelled.

We have not yet been able to trace any record of the commissioning of the work, but the bust (pictured above) which is signed but not dated, was exhibited at the Manchester Academy of Fine Arts Spring Exhibition in 1910, and has been in the University of Manchester at least since the 1940s. Above is a detail from a photograph of a meeting of the University Senate in 1944, with the Hopkinson bust on its wooden plinth visible in the background; by the 1970s it had been transferred to the University School of Law, where it stands in a student common room, normally open only to students and staff of the School.

Glimpsed in the corner of the picture is 'Socrates teaching the people in the Agora' by Harry Bates (1850-1899). a marble relief purchased by the College in 1886. This is one of the most important sculptural works in the University's collection.

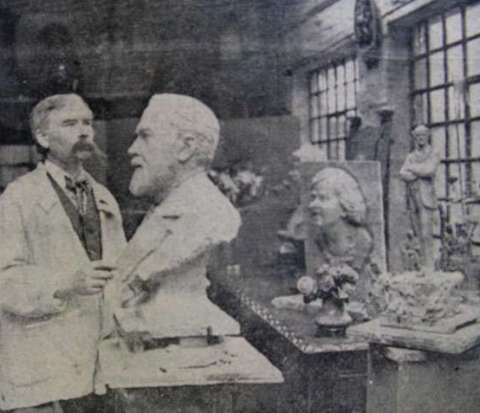

A photograph (above) taken in Cassidy's Lincoln Grove studio in 1910 shows him with the clay version for a memorial bust of the Reverend J. Hirst Hollowell. Among the assorted objects in the background can be seen the model for a statuette of Hopkinson, which was later cast in bronze dated 1913 - pictured below and in the left column. This was not the only time that a statuette as well as a bust was created by Cassidy; both versions exist of Cassidy's portrait of musician Charles Hallé. (We have been unable to identify the female head seen in the picture.)

Above, a closer view of the statuette, which is just 19 inches high. Notice that it differs from the bust, in that he is portrayed looking slightly to one side. This work was exhibited at the Manchester Academy of Fine Arts in Spring 1914, and also in Cassidy's own exhibition at his Lincoln Grove studio later that year.

Many years later it appeared in auction at Christie's, South Kensington on 13 November 1991 as Lot 97: 'Figure of a gentleman, his arms crossed.' Estimated at £800 - £1200, it failed to reach its reserve and was not sold; at the time of writing (2012) it is the only Cassidy work for which we have been able to discover a modern auctioneer's valuation.

It still exists in 2012, in the care of a great-grandson of Sir Alfred.

Map showing York Place and Grove House in the 1890s. Oxford Road with its tram lines runs from north to south across the view. Cassidy's statue of King Edward VII, installed in 1913, stands at a point just to the west of Oxford Road approximately at the point where it crosses the southern edge of this map.

Alfred Hopkinson: his life and times.

Alfred Hopkinson was educated at a private school in Manchester and attended Owens College from 1866. In 1869 he won a scholarship to Lincoln College, Oxford, where he was placed in the second class in literae humaniores in 1872 and in the first class in the BCL (Bachelor of Civil Law) examination in 1874. He was elected to the Stowell fellowship in civil law at University College, Oxford, in 1873, and to the Vinerian scholarship in 1875. In 1873 he married Esther, youngest daughter of Henry Wells of Nottingham; they had four sons and three daughters.

Hopkinson was called to the bar by Lincoln's Inn in 1873 and returned to Manchester where he established a practice as barrister. In addition he was lecturer at Owens College, and in 1875, at the age of just twenty-four, was made Professor of Law.

In 1885 and 1892 he stood, unsuccessfully, as a Liberal parliamentary candidate in Manchester. He moved to London in 1889; the 1891 census found him in 'The Lodge', Herne Hill, living with his wife, seven of his children (Arthur, John, Ellen, Alfred, Margaret, Martin and Esther) and four servants. He took silk (became a Queen's Counsel) in 1892, and was elected MP for Cricklade in Wiltshire in 1895, only to resign the seat in 1898 on his appointment as Principal of Owens College. Returning to Manchester, he moved his family to a house Daisy Bank Road, Victoria Park, which he named 'Fairfield' - almost certainly after a famous mountain in the Lake District, all the Hopkinsons loved hill walking and climbing. The house later became a 'guest house' for students for some time, and was eventually replaced by a modern block of flats known as 'Fairfield Court'.

He was awarded a knighthood in 1910. Retiring from the University in 1913, after overseeing great changes, Hopkinson devoted himself to public service. His activities included visiting India to report on the University of Bombay, and at a by-election in 1926 he returned to parliament as Unionist MP for the Combined English Universities, finally retiring in 1929.

Alfred and Esther had four sons and three daughters. Two of their sons entered the Church, whilst their son Austin Hopkinson became an industrialist and a leading citizen of the town of Audenshaw just south of Manchester, serving on Audenshaw Council from 1917 to 1934. He instituted a profit-sharing scheme for his workers, and converted a derelict barn to a bungalow for his own home and in 1922 donated his former home of Ryecroft Hall (which he had bought in 1913 from the Buckley family for whom it was built in the 1850s) to the people of Audenshaw and sixteen semi-detached houses on its land to Audenshaw Council. He also served as a local MP for some years and had some interesting ideas; in 1922 he wrote to The Times to suggest that ballot papers include a box in which voters could express their disapproval of all the candidates on offer. He is commemorated today at Ryecroft by a blue plaque.

Alfred's daughter Margaret Hopkinson married Gerald Hurst, a lawyer and politician who makes an appearance in one of the author's articles on another website, our chronicles of the history of the Stockport suburb of Davenport. His autobiographical book Closed Chapters is worth reading by anyone interested in Manchester life of the period.

Alfred's son John Henry Hopkinson (1876 - 1957) studied at the British School at Athens and was a lecturer in classical archaeology at the University of Manchester from 1904 to 1914. He was also the first warden of Hulme Hall, built in 1907, one of the first purpose-built halls of residence for students of the University of Manchester, built for the Church of England to replace earlier premises at 174 Plymouth Grove.

Described by his biographer as 'a man of striking physical appearance and great personal charm', Alfred Hopkinson was a principled man with a deep-rooted belief that 'the hope of mankind is in the Christian religion.' His beliefs and theories were expounded in his book Rebuilding Britain: a Survey of Problems of Reconstruction (1918) and his autobiographical memoir Penultima (1930).

He died at 'Long Meadow', Bovingdon, Hertfordshire, the home of his son Martin (of publishing company Martin Hopkinson Ltd) on 11 November 1939.

Hopkinson on ...

... Work

There is no doubt that among the causes of unrest one of the most serious, probably much more so than either employers or workmen are generally conscious of, is the long hours of work. Those who have had to hear questions arising out of labour disputes have noticed the state of tension produced by the weariness and strain of too prolonged and continuous work.

Even in the domestic circle an overworked man is often found less amiable and more ready to find fault. A harassed manager and a deputation of jaded workmen may be really very good fellows and yet find that some comparatively small question raises strong feeling and mutual recrimination, and then leads to rash action resulting in open strife, strikes, and lock-outs, and the judicial proceedings which may be necessary in consequence of them ... Man cannot be looked on as a mere machine for production, nor is even health the only question for him as a human being. He must have time for other pursuits, for recreation, for a fuller life. As civilisation and education advance this need becomes stronger. The duller the work the greater the need for those who have any natural mental activity to find resources of interest outside. The pleasure derived from literature and science should be open to all.

... Religion

There is a deep truth in a remark once made by the late Bishop of Manchester, Dr. Moorhouse, when speaking of possible co-operation on a certain matter between people belonging to different religious communities: "It would be so easy did we only recognise how large is the area covered by things on which we agree, how important they are, compared with those on which we differ."

... Democracy

We know by experience how the vote of a popular representative assembly may represent the opinion of "a bare majority of a bare majority"; conceivably anything over one-eighth of the nation. A committee is elected by some eager partisans supposed to represent a party. That party perhaps represents a bare majority of the constituency. The caucus chooses a candidate whose views suit a bare majority of its members who hold the most extreme views. He and others go to Parliament as representing one party, and a majority of such members decides what policy shall be adopted. Party discipline compels the acquiescence of the rest. The machine is cleverly constructed to make the will of certain party managers of mere sections of the constituencies the dominant factor. No wonder that they denounce Proportional Representation as a dangerous fad.

Quotations from Rebuilding Britain (1918).

The signature on the side of the bust.

'The dustheaps of Egypt are ransacked for any scraps which throw light on the lives led beside the Nile centuries ago, but how few really take pains to understand exactly the though, the ideas and habits of their grandfathers in their own land.' - Sir Alfred Hopkinson, in Penultima, 1930.

Special thanks ...

... to everyone who helped with the creation of this feature: Jonathan Hopkinson for the information and pictures of the statuette; Sheila Dewsbury of the Manchester Academy of Fine Arts for arranging access to the archives including the studio photograph; Peter Wadsworth of the John Rylands University Library for locating the bust; and the staff of the University School of Law for permission to visit and photograph the work.

Written by Charlie Hulme, March 2012.