It is appropriate to write this feature in August 2019, as the events in Manchester in August 1819 have immortalised the name Henry Hunt in the annals of Manchester.

Although mentioned in passing in Terry Wyke's book, the location of the work eluded us for some time, until we found a reference to it in the Manchester Region History Review as being in the Manchester Museum of Science and Industry.

In 2011 we tracked it down in the

basement of the original buildings of Liverpool Road

railway station, which forms the museum site, in an

series of rooms dedicated to the history of the city

entitled 'The making of Manchester.' It was located in

an awkward position directly below a window which

disrupted the camera exposure, and other exhibits

opposite made it impossible to photograph face-on with

the widest angle our camera could manage. The

image above is the best we could do; the main image on

this page is from the Museum's own collection.

The caption made no mention of Cassidy, as seems to be the norm when sculptures are used in a historical context as an illustration of the subject. The Museum's other Cassidy, James Southern, in the same gallery, was also devoid of an attribution.

In 2015 the Making of Manchester exhibition was dismantled, on the ground that it had become 'stale', and its artefacts disappeared into store. Around the same time, Manchester Art Gallery removed its local history-based exhibition which caused Cassidy's work 'The Digger' to vanish from view.

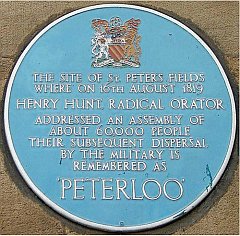

In 1972 a blue plaque - blue is for people - was mounted on the wall of the Free Trade Hall commemorating Henry Hunt, but without details of the deaths and injuries, leading critics to describe it as 'mealy-mouthed'.

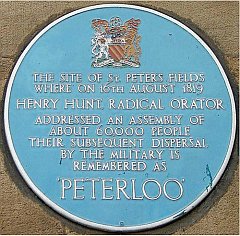

In 2007 it was replaced by a red one - red for events - with no mention of Hunt but detailing the deaths and injuries. By that time the Free Trade Hall - or at least the front of it - had become a Radisson hotel.

The caption made no mention of Cassidy, as seems to be the norm when sculptures are used in a historical context as an illustration of the subject. The Museum's other Cassidy, James Southern, in the same gallery, was also devoid of an attribution.

In 2015 the Making of Manchester exhibition was dismantled, on the ground that it had become 'stale', and its artefacts disappeared into store. Around the same time, Manchester Art Gallery removed its local history-based exhibition which caused Cassidy's work 'The Digger' to vanish from view.

Plaques old and new

In 1972 a blue plaque - blue is for people - was mounted on the wall of the Free Trade Hall commemorating Henry Hunt, but without details of the deaths and injuries, leading critics to describe it as 'mealy-mouthed'.

In 2007 it was replaced by a red one - red for events - with no mention of Hunt but detailing the deaths and injuries. By that time the Free Trade Hall - or at least the front of it - had become a Radisson hotel.

Sources

'Henry Hunt' on Spartacus educational'Peterloo Recalled: A Memorial to "Orator" Hunt.' The Manchester Guardian 30 Jun 1908 p. 7.

Henry Hunt bronze plaque. Science Museum Group collection. The image of Henry Hunt is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence.

'Peterloo memorial quietly unveiled three days before anniversary'. The Guardian, 13 August 2019

Website created and compiled by Charlie Hulme and Lis Nicholson, with the invaluable assistance of the John Cassidy Committee, Slane Historical Society.

Henry Hunt (1908) and Peterloo

The inscription reads: Henry Hunt who for his part in the Great Reform Meeting in St Peter's Fields on Aug 16 1819 suffered two years' imprisonment.

Henry Hunt and Peterloo

Henry 'Orator' Hunt, was born in Upavon, Wiltshire, on 6 November 1773, the son of Thomas Hunt, a gentleman farmer. Educated at the local grammar school, Henry joined his father in looking after the family estates. On his father's death in 1797, he inherited 3,000 acres in Wiltshire as well as a large estate in Somerset. In 1800 Henry Hunt became involved in a dispute with a neighbour who took Hunt to court; he was found guilty and sentenced to six weeks imprisonment. During his court case, Hunt met Henry Clifford, a radical lawyer who was involved in the campaign for adult suffrage, and after moving to Surrey was inspired to enter the political arena, developing a talent for oratory.In 1816 he spoke at large reform meetings at Birmingham, Blackburn , Nottingham , Stockport and Macclesfield, which attracted huge crowds, and in 1818 he entered Parliament for the Westminster constituency. On 16 August 1819, he and Richard Carlile, one of his supporters, arrived at Manchester to speak at an open-air gathering in St Peter's Fields, near what is now known as St Peter's Square. Many thousands of people - estimated at 80, 000) from Manchester and surrounding towns had travelled there to hear him speak (or at least see him from a distance.)

However, the Manchester magistrates had other ideas, and considered him dangerous; it was decided that he should be arrested. Not a quiet arrest before he reached the podium, but when he was in position and about to begin speaking. The local Yeomanry (part-time soldiers) attended to assist with the arrest, and they moved through the crowd on horseback to reach Hunt and his colleagues, injuring a woman and killing a child. They were followed by soldiers of the 15th regiment of Hussars summoned by the Chairman of the Lancashire and Cheshire Magistrates, William Hulton, to disperse the crowd. They charged with sabres drawn, and in the ensuing confusion, 18 people were killed and an estimated 400 - 700 were injured. This became known as the 'Peterloo massacre' in analogy with the battle of Waterloo which took place four years earlier.

Henry Hunt was found guilty and sentenced to two and a half years imprisonment, and when released continued to campaign until his death in 1835. The overall effect of Peterloo in the struggle for political reform is still debated by historians, although it did lead directly to the foundation of the Manchester Guardian newspaper (much later re-named The Guardian) in 1821. The Reform Act of 1832 constituted a start, but it was rejected by Hunt as it did not include universal (male) suffrage, only men owning a certain value of property could vote in national elections. It was not until 1918 that this restriction was completely removed.

The Memorial

Henry Hunt was not recognised by any memorial (although a commemorative medal was struck and distributed) in Manchester until 1842, when an obelisk was erected in the old burial ground of Scholefield's Chapel in the confusingly-named Every Street, Ancoats. When the Chapel was sold and the burial ground converted to a recreation ground in 1888 the obelisk, which had fallen into disrepair, was dismantled. It had been designed to have a statue of Hunt on the top, but it seems this was never done.An appeal was launched to fund a new memorial, and some money was collected, but the project petered out and it was another twenty years before anything was done. Finally, it was decided to commission John Cassidy to create a bronze memorial in the form of a plaque (a medallion in the technical terms of the day) and this was completed in 1908 and installed in the vestibule of the Reform Club, after a plan to place a memorial in the Free Trade Hall was abandoned.

The medallion was unveiled by C.P. Scott, editor of the Manchester Guardian, and his speech was reported by the Manchester Guardian . He commented on Cassidy's involvement:

The bulk of the money collected had been expended on the interesting and life-like medallion , the works of a talented Manchester man, Mr. Cassidy, to whom the subscribers were greatly indebted, for Mr. Cassidy had done the work largely as a "labour of love", and had produced a worthy memorial to one who deserved to be remembered.Perhaps this gives us an inkling of Cassidy's own political leanings, or perhaps he simply hoped that paid work would come his way from the illustrious members of the Reform Club.

Of Henry Hunt, Mr Scott commented:

Hunt deserves a memorial in Manchester. He was not, perhaps, a very great man. He certainly was not a man as fine character as Samuel Bamford, who was his follower at that time and led a contingent of 3,000 men from Middleton. But he loved the people and was a stout defender of their liberties. Therefore it behoves us who seek to uphold the same cause, to near his name in memory.We are not told why there was opposition to a memorial in a public place rather than the wall of a private clubhouse, but it is true that nobody in Manchester ever heard his oratory.

in 1987 the Medallion found its way to the Museum, and became truly public for the first time, although one can't help thinking that few visitors ever gave it more than a glance. It cannot be said to one of Cassidy's finest works, but perhaps it deserves to see the light of day once more.

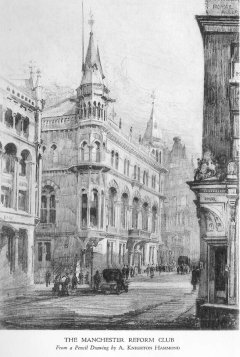

The Reform Club

The Reform Club was a 'gentleman's club'

established in 1867 for men of a Liberal political

inclination. In 1967 it merged with the Engineers'

Club to form the Manchester Club, which itself closed in

1988. The Club building on King Street, opened by Foreign

Secretary Earl Granville in 1871, still stands, a

Grade II* listed building. Designed by Manchester architect

Edward Salomons in a style described at the time as

'Venetian, freely treated', it was used as offices for

a while, with the Manchester Club occupying part of the

building until it folded in 1987; more recent occupants have

included shops, bars and restaurants, including the

'notorious' Reform restaurant, 'a haunt of Manchester

football and television celebrities'. in 2019 it is

'Grand Pacific', described as 'a Pacific rim/pan Asian

eatery with a dash of Raffles Hotel glamour'. Like

much of central Manchester, the building is owned by the

Bruntwood group.

The Reform Club was a 'gentleman's club'

established in 1867 for men of a Liberal political

inclination. In 1967 it merged with the Engineers'

Club to form the Manchester Club, which itself closed in

1988. The Club building on King Street, opened by Foreign

Secretary Earl Granville in 1871, still stands, a

Grade II* listed building. Designed by Manchester architect

Edward Salomons in a style described at the time as

'Venetian, freely treated', it was used as offices for

a while, with the Manchester Club occupying part of the

building until it folded in 1987; more recent occupants have

included shops, bars and restaurants, including the

'notorious' Reform restaurant, 'a haunt of Manchester

football and television celebrities'. in 2019 it is

'Grand Pacific', described as 'a Pacific rim/pan Asian

eatery with a dash of Raffles Hotel glamour'. Like

much of central Manchester, the building is owned by the

Bruntwood group. A new memorial

A new

Peterloo memorial created by Turner Prize-winning artist

Jeremy Deller and architect Caruso St John, was installed

near the Manchester Central conference centre, on the site

of St Peter's Fields, in August 2019, and revealed to the

public without ceremony, three days before the anniversary

of the massacre. The monument, said to have cost a million

pounds, is made up of eleven concentric steps featuring

carved names of the people who died and the towns from which

they travelled. The idea behind the design was that people

would walk to the top of the monument and use it as a

speakers’ podium, although critics pointed out that there

was no access for the disabled, and changes were to be

discussed. The adjacent disc on the ground has compass

arrows pointing towards the scenes of other famous massacres

of political protestors around the world.

A new

Peterloo memorial created by Turner Prize-winning artist

Jeremy Deller and architect Caruso St John, was installed

near the Manchester Central conference centre, on the site

of St Peter's Fields, in August 2019, and revealed to the

public without ceremony, three days before the anniversary

of the massacre. The monument, said to have cost a million

pounds, is made up of eleven concentric steps featuring

carved names of the people who died and the towns from which

they travelled. The idea behind the design was that people

would walk to the top of the monument and use it as a

speakers’ podium, although critics pointed out that there

was no access for the disabled, and changes were to be

discussed. The adjacent disc on the ground has compass

arrows pointing towards the scenes of other famous massacres

of political protestors around the world.Written by Charlie Hulme, August 2019.

Comments welcome : charlie@johncassidy.org.uk